Circle members Neil Fairlamb, Justin Keay and Stephen Barrett voyaged into the wine regions of northern Italy on a Circle trip to Emilia-Romagna from 31st May to 2nd June. They share their experiences of this delicious corner of Italy, from the underrated delights of Pignoletto (both in its bubbly and still rendition) to the tempting trattorias and delectable cuisine of the region.

Neil Fairlamb thanks our hosts for a brilliant visit to Bologna and the wine regions of Emilia-Romagna. He then discovers the considerable appeal and potential of Pignoletto, especially in its sparkling form.

Our very grateful thanks go to Consorzio Pignoletto and Consorzio Vini Colli Bolognesi, and to Jacopo Cossater for all planning and liaison, and to Debora Marchesini for travel arrangements. This excellent, concentrated trip which managed to include city centre discovery, individual restaurants very focused on local food, stunning walks through dramatic landscapes and a strong sense of gastronomic culture. We were fortunate to have the wise guidance of Carla Capalbo, also a Circle member, in coordinating all our activities and with her deep knowledge of the region and the food and wine synergies that are possible in Emilia-Romagna we had an excellent time.

The day before the Circle of Wine Writers visit, the rain stopped-after a month of exceptionally heavy rain which had sodden the ground, washed soil and debris down the hills, spoilt our swimming pool in a luxury B&B (Pragatto Hills), and made the normally succulent strawberries watery and tasteless. May 2019 brought more rain in one month than in the whole of last year. We brought the sun and everyone was glad to see us.

Our very first day saw the extremes of winemaking in the region: huge scale production of sparkling wine and a small biodynamic wine producer, from the region but with years of experience in Brazil behind him, making biodynamic white wines of uncompromising style: unfiltered and cloudy, sharp in acidity and strong in tannins. Not just a winemaker too, but a pig keeper – of the indigenous breed of Mora Romagnola, who were revelling in the muddy conditions. From them is made the best mortadella ever – every other version pales by comparison, in colour and taste. But let me begin with the last day which gave a comprehensive overview of the region’s efforts with its best and indeed unique white wine grape.

Bologna is in the centre of the Emilia-Romagna region, where there is one wholly individual wine which deserves a definite place in the list of underrated or unknown varietals – Pignoletto. From Modena, southeast past Bologna and towards Imola and Ravenna, there is a wide variety of styles and winemaking approaches. A professionally prepared tasting of 54 Pignolettos superbly organised by Jacopo of the Consorzio, with the fullest information on each wine carefully prepared, and kindly hosted by the Santacroce winery, was as thorough an immersion into the possibilities of this varietal as one could wish for, and the results were impressive. It definitely has something to say, both as a much better sparkling wine than most Prosecco or its alternatives, and as a still wine with more personality than many Italian whites.

There were 40 sparkling wines, made by the frizzante and spumante methods, and 13 still wines. Although all the latter are DOCG, there are two subcategories: Superiore and Superiore Classico. The sparkling wines, by whichever method, are either DOC Pignoletto or DOCG Colli Bolognesi Pignoletto – basically the former for the clay-dominated flat lands of the plain, with the DOCG for the higher slopes where the argille soils can help produce wines of more perfume and fruit.

The still wines, although only 5% of production, best revealed the full character of the grape, and immediately one could see how greatly more characterful this variety is than the Glera of Prosecco. Such charms as the Glera has would be seriously compromised if made into a straight dry wine; it just doesn’t have the structure or depth as a varietal and is best vinified as a sparkling wine for immediate consumption, as the whole world knows.

Taming those tannins

Pignoletto has personality: citrus and herbaceous aromas strike one on the bouquet, with notes of pear and white peach. What immediately emerged was the striking level of tannin in the Pignoletto when vinified dry and skin contact is emphasised. It is a thick-skinned varietal and, with older vines cultivated on calcareous clay or silty soils, the wines have a surprising full-flavoured depth. The challenge is not to let the tannin dominate, but certainly for it to contribute to the texture of the wine, backed up by green apple acidity. These are quite serious wines, though probably mostly at their best within three years of the vintage.

Of the style emphasising maximum flavour, Balli Vini’s 2017 was almost too weighty but very full flavoured from a four-hectare (ha) plot and using 20-year-old vines. A finer balance was struck by Nugareto’s Cantastorie 2017, an organic wine with a harmonious woven texture, and Carpi e Sorbara’s 2018, less intense but good value at €3.5 (others mostly €6-7).

The other main style is to emphasise crispness and good attack on the palate with positive acidity, avoiding heaviness. This style will win many friends to the varietal, if not expressing its full potential. Guggioli’s 2018 was made in inox but left on the lees to refine and gain complexity. Tizzano practised destemming and a little barrique helped fill out a well-balanced finish. I particularly liked Podere Rosto’s 2017, produced quite high up at 350 metres on piocene sand/silt and clay – with good drive and attack, and very lively in the mouth. Even better was Montevecchio Isolani 2017, another organic wine, whereby the grapes were grown on sandy clay with rounder, fuller flavours.

The star of the show, though, and from the Superiore zone, was Ammestesso 2014 from Vallona, a step up in price to €10 at the cellar and well worth it. The average age of the vines is 15 years, and they grow on calcareous marl at about 300 metres. The wine spent three years in cement tanks, with lees stirring and fining throughout this time. This had perfect texture, and it was rounded and beautifully silky, but fresh tasting and perfectly poised – a pleasure to drink also at the Michelin-starred Trattoria Amerigo later that day.

Other good Superiore wines included a solid Alto Vanto Bianco from Aldrovandi, made from old vines in a 1ha plot and fermented in barrique, which was a weighty wine of good density and fullness, as was Terre di Montebudella from la Mancina at its mature 2016 best. These Superiore wines included a fresh Maneresi 2017 organic wine and a 2017 d`Estro from Botti with 10 months on the lees to extract a strong wine (14% like Vallona`s) – organically made, and nutty complexity showing evolution. Sit a Montui 2016 from the host winery, Santacroce, from mature vines and sur lie for 8 to 9 months, was typical of the added complexity of these Superiore wines.

I felt these still wines were overall very well made and had real personality, and were much more complete wines than expected, and they served to show the interest of this varietal. Skill in winemaking is needed to balance the acidity with the tannins of the grape skins, which can get out of balance.

Exportable bubbles

The frizzante and spumante expressions of this varietal have the biggest export appeal at present, although exports are less than 10% of production. The former style, re-fermented in the bottle with less sparkle, still seems to me a gentler and more expressive style – the ancestral method – but for export the spumante made by cuve close/Charmat is inevitably going to be more popular, and many consumers would still resist a cloudy wine, however full the flavour.

The huge volumes that are produced on the clay flat lands with alluvial soil near Modena by well-placed big companies like CIV Riunite are impressive and the wines have much more personality than most Prosecco. The grape variety simply has more polyphenols than the Glera of Prosecco. Two are produced by Cavicchioli under the CIV umbrella for the UK market as own-label and the difference between Sainsbury’s selection and Tesco’s is that the latter is 11.5% and made from riper grapes than the former at 11%. Perhaps Sainsbury’s choice is competing on alcohol with Prosecco and not getting to Cava and other rival alcohol levels, but the Tesco version seemed the more complete wine. CIV Riunite produces a whole raft of styles including organic; particular favourites of mine chez Cavicchioli were Arès, Fratelli Bellei and Senzatempo, all of which had a distinct personality and tangy flavours with rounder balance. Terre Felsinee from Argelato also succeeded in making a weightier, fuller-flavoured wine no Prosecco could compete with.

Size can have its advantages; the region suffered earthquakes in 2012 and GIV could help with investment in recovery and replanting.

An outstanding individual producer was Cleto Chiarli, whose frizzante Vecchia Modena I preferred to the two good spumante versions; a combination of 80% soft pressing of whole destemmed grapes with 20% of the grapes with a 12-hour maceration seemed carefully judged. One is looking for the right measure of attack and refinement, neither too soft nor too heavy.

The wines from higher altitude, DOCG Colli Bolognesi have, perhaps, more personality and individuality, some like Nugareto’s Giulare, requiring food to complement the full flavour. Il Monticino’s frizzante had structure and firm balance, as had the spumante Cuvee Nettuno from Santacroce, as did the Montevecchio Isolani wines from the Consorzio’s president. I’m not sure if 42 months on the lees worked quite so well for Tenuta La Riva; the deep colour and weighty flavour were a little less than refreshing. This, however, was a very interesting winery with lots of experiments and a modern approach. One to watch.

The problem with Pignoletto, or is that Grechetto Gentile?

There remain some problems for marketing. Everyone knows Prosecco but few register that it is made from the Glera grape. Pignoletto is the grape variety of Emilia-Romagna but the authorities want to use the name for the style of wine as a rival to Prosecco and officially decree that the grape be called Grechetto Gentile or Alionzina as a local name. This is confusing as it is not the same Grechetto as found in Umbria.

Our visit gave a strong sense of both the landscape and the gastronomic culture. There were dramatic vineyard sites at Monteveglio and Montemaggiore where the remarkable calanchi geological rock formations framed some beautifully sited steep vineyards with tempting walking trails. In Bologna, we went to a farmers’ market, Mercato Ritrovato, where consumers could revel in distinctive products made by the best traditional methods, and a food kitchen outlet for what was left over for the city’s less fortunate. The organic wines of Federico, our host at Pragatto Hills, and friends were there at the market and part of a happy sharing of ideas and creativity in food and wine partnership. Wandering through the endless porticos of Bologna’s distinctive city centre was also an induction into foodie heaven.

Federico’s own wines from 10ha owned and 5ha leased (60,000 bottles in all annually) – Orsi Vigneto San Vito – were uncompromisingly challenging: the white wines were cloudy, the lees (sui leviti) remaining in the bottle to keep the wine fresh, and so neither filtered nor disgorged. They certainly had plenty of character but in a vertical tasting of six vintages the two lighter years, 2014 and 2010, seemed to be more successful – fresh but intense wines and successful if uncompromisingly dry, whereas other years had too much grippy tannin. Of three blends of Pignoletto with other grapes, I much preferred the Malvasia to Albana and Alionsa, both of which seemed to add to the acidity balance and not reduce it. His still Pignoletto Vigna del Grotto Superiore Clasico was very successful: aromatic, minerally intense and very long.

He makes also a white and red called Posca by the solera method, taking 5-10% or so each month for bottling and topping it up from tanks of younger vintages. It’s surprising this method is not done more often, mixing mature and fresh wines, a sort of vina perpetua. The current solera started in 2008. These wines are popular with clients and less expensive. His grape variety mix does change, and so will the Posca taste; he is, for example, pulling up an old Cabernet Sauvignon plot and replacing with indigenous red varietals like Barbera, Sangiovese and Negretto. Federico’s straight Barbera 2016 from the top of the hill, was intensely aromatic after 12 months in Slovenian oak, and the blend of Barbera with Negretto made with one-month skin contact was smoky, textured and grainy.

From Prosecco to Pignoletto: is it time for the UK to embrace a new P…o from Italy?

Justin Keay ponders why Pignoletto’s fine sparklers haven’t quite exploded onto the British market, at least not yet. A version of this article was earlier published at The Buyer.

If anyone ever comes to write the definitive account of contemporary Italian wine, they should include a hefty section on former bulk wine regions that have overhauled their reputations.

Over the past decade, Abruzzo, Le Marche and Molise – to name just three – have taken this route, with tired cooperatives making way for younger, more dynamic producers prepared to work with indigenous varieties, and to prioritise quality over quantity. Emilia-Romagna is following suit with local wine Consorzios keen to see local producers attain a quality level that will let the industry stand proudly alongside the region’s famous gastronomy, one of Italy’s most outstanding.

Colli Vini Bolognesi Pignoletto DOCG was actually established back in 2010, the second DOCG to be set up in Emilia-Romagna, covering a hilly area between Bologna and Modena. It is focused on the area’s traditional sparkling wine, which comes in spumante and frizzante style, although Pignoletto is also made successfully here as a quality still wine (Superiore and Classico Superiore). And it has been on a big export push, with producers keen to find new markets abroad: currently just 10% of production is sold abroad.

Curious, I decided to judge for myself what strides Pignoletto has made towards quality in a DOCG where a well-regarded wine encylopedia suggests, “few producers aim for quality as most Pignoletto ends up in the tanks of large bottlers and huge cooperatives”.

Although Pignoletto is actually grown in a much wider area – indeed, pretty much all the way across to Rimini, in the east and to the west, beyond Modena (home to another famous sparkling wine, Lambrusco) – Colli Bolognesi is home to the quality end of Pignoletto. In essence, the DOCG is to Pignoletto what Asolo and Conegliano-Valdobiaddene are to Prosecco. However, the Consorzio – which this being Italy, works alongside another Consorzio (Consorzio Pignoletto Emilia Romagna) to promote the wine internationally – isn’t too keen on comparisons.

“Actually, we don’t wish to compete with Prosecco but maybe Pignoletto could become a good alternative. We don’t produce anywhere near the same amount so there couldn’t be (serious) competition. However, Pignoletto has more complexity and better features and Grechetto Gentile can be used to make sparkling, still and even passito wines,” says the Consorzio’s director Giacomo Savorini, suggesting – as many here do – that the variety used to make the wine is superior to, and more nuanced than Glera, the Prosecco grape.

For this reason perhaps – or because Brits have become conditioned to love sparkling wine that begins with P and ends with O – Pignoletto is doing well in the UK off-trade, most notably at Sainsbury’s, which sells an 11%, Prosecco-like spumante usually at a discounted price of around £6 – and Tesco, which sells a slightly higher end version with 11.5% ABV in its Finest range for around £8.50. (Both own-label wines are in fact made by the same large producer Cavicchioli, which also makes a range of Lambrusci).

Waitrose also sells an extra dry 11.5% spumante Vecchia Modena produced by Chiarli 1860 – made to the west of the Colli Bolognesi DOCG – for around £10 when not on discount, and the wine gets consistently high ratings.

Some in the industry say Pignoletto’s time has come. Steve Daniels of HN Wines which sells a frizzante Pignoletto from Colli d’Imola – a moreish, well-priced, fruit forward wine perfect for summer drinking – says sales are up 50% on last year. He reckons the outlook is similarly good, although he admits “nothing will ever be as big as Prosecco again.”

“Pignoletto is a fantastic drink; more mineral, complex and food-friendly than Prosecco and it provides far better value for money, as Glera grapes from DOC and DOCG areas are so expensive,” he argues. Pignoletto also has the advantage that it is widely available in the frizzante style – popular in Italy because of its food-friendliness but relatively scarce in terms of the Proseccos imported to the UK.

Yet for some importers, it just hasn’t taken off. At a recent Berkmann Wines Italian tasting, I was surprised to see that although lots of high quality Prosecco and Franciacorta were in evidence, Pignoletto was quite absent. “You know what? We never seriously thought about it – maybe because the supermarkets are offering such great Pignoletto already,” says head buyer Alex Hunt.

BBR? The same story. Likewise Armit and Winetraders, the Oxford-based single estate Italian specialist run by Michael Palij; they offer a great Lambrusco made by Vittorio Graziano outside Modena but again, no Pignoletto.

Winchester-based Stone, Vine & Sun used to offer a great Colli Bolognesi Pignoletto – Floriano Cinti – which for me really stood out at the importer’s Christmas tasting. Yet it hasn’t done well, and owner Simon Taylor says he has been obliged to stop importing it. “The wine was brilliant but only a few people liked it [and they liked it a lot]. I don’t think we ever sold more than a dozen to any single person. And no on-trade either. Prosecco still rules,” he says.

So what’s the problem?

Quality isn’t a concern, as a tasting of 55 sparkling, frizzante and still wines organised by the Consorzio confirmed. Quite a few of the Colli Bolognesi Pignoletto DOCG wines in particular stood out, with Tenuta Santa Croce, Montevecchio Isolani (a historic producer coincidentally owned by Consorzio President Francesco Cavazza) and Fattorie Valona scoring very highly for quality and accessibility (the latter also makes an impressive range of still wines notably using Cabernet Sauvignon but also some of the region’s largely forgotten native grapes like Negretto and Vigna del Fantini).

An absence of big producers is likewise not a problem: although there has been some movement, Pignoletto is still dominated by large families, coops and former coops, who bring economies of scale, without forsaking quality, to their wines. Cavicchioli, for example, produces over 10 million bottles yet retains a strong quality profile.

But a lack of internationally known names – notably those active in other more highly regarded wine regions in Italy who could show the way forward for Pignoletto – is clearly an issue. Coupled with the failure of excellent local producers like Vallona and Monteveccio to become better known outside Emilia-Romagna, it might be one reason Pignoletto hasn’t made more inroads into the on-trade.

“Actually, it is the biggest problem: our aim in coming years is to add value to our soil to make the entire region more attractive for big Italian investors and producers,” says Giacomo Savorini.

Another priority should be to clarify the marketing message, which has if anything been muddied by recent changes. Pignoletto used to be made from the Pignoletto grape, but no longer – in an effort to preserve the name for the product, the variety has been renamed Grechetto Gentile (not the same variety as Umbria’s Grechetto) but is also known locally variously as Grechetto di Todi and Alionzina. In an effort to provide some sort of origin backstory, a tiny local village in the heart of Colli Bolognesi is now called Pignoletto. All this though is rather confusing for consumers who just want a good drop of sparkling wine.

For Steve Daniels, time may play to Pignoletto’s advantage. “Pignoletto can certainly gain a larger foothold in the UK if Bologna takes off as a tourist destination and this drives its local produce. There is no reason it shouldn’t – it is the gastronomic stomach of Italy and the cuisine is world-renowned. Pignoletto, alongside Lambrusco, are the local wines which go very well with the local food,” he says, adding: “Give me a Pignoletto over a Prosecco any day.” I couldn’t agree more.

Over the three days I tasted my way through the Colli Bolognesi, I came to realise just how nuanced Pignoletto can be, with some of the smaller producers – up to 100,000 bottles a year – some of the most ambitious in terms of pushing the quality and stylistic envelope. Some of the DOCG wines were particularly innovative with producers from higher elevations – like Nugareto – making sophisticated wines that really need food to bring out the best; by contrast Tenuta La Riva makes a weighty Pignoletto that has spent 42 months – that’s right – three and a half years – on the lees.

Meanwhile some producers like Orsi/Vignetto San Vito have unashamedly gone the natural wines route making sometimes cloudy, often challenging wines that would be snapped up in Hoxton Square or other hipster joints in an instant, but which are genuinely appealing even to us squarer, more mature folk who occasionally yearn for something different.

Indeed, even the more bog standard Pignoletti – mainly those from the Pignoletto DOC rather than the Colli Bolognesi DOCG – have a freshness and character to them that mainstream Prosecco from say the Treviso region completely lack, with the broad fruit flavour profile of Grechetto Gentile tending to produce a far more satisfactory wine. And then there are the still wines, many of which spend time in barrique and thus show a completely different side to Pignoletto.

All of which suggests that Pignoletto’s curiously low profile in the UK on-trade won’t last for long. With some much innovation taking place – especially within the Colli Bolognesi DOCG – it seems clear that Pignoletto’s best days are yet to come.

Indulging in a slow food movement through the wine regions of Emilia-Romagna

Stephen Barrett tucks into the delectable culinary offerings of Emilia-Romagna that were creatively served up to our visiting party, culminating in an unforgettable evening at a Michelin-starred trattoria.

With a great reputation for fine food, it was with great anticipation that we observed and enjoyed the endless possibilities served up in the Emilia-Romagna region.

Our excellent hostelry – Casino di Pragatto – for the duration couldn’t have been better with spacious modern rooms, facilities and outstanding woodland views. Our first wine tasting (alfresco) was later integrated into the beautiful dining room facilities of Casino di Pragatto. Our caterer was the noted Belinda Cuniberti of Enoteca La Zaira, who obviously knew the seasonal produce very well, offering us a gracious supper of exquisite delights, including asparagus, tortilla, local squash, parmesan and blue cheese, tortellini ricotta, artichokes, polenta and aubergines – all separately prepared and offered in series with the different wines! The garden salads were a real hit with organic produce and edible flowers literally everywhere! As the wines (with commentary from the winemaker and chef) were offered, the dishes matched with great understanding.

Our next day, which began in Bologna, was spectacular with an excellent guided tour (top guide!) of, amongst other places, the San Petronio basilica and the unique medieval university with its tall towers and narrow streets, wide boulevards and interactive markets. The smell of coffee and chocolate were all part of the stroll around this great city. Spotting many outstanding trattorias and restaurants, we wondered where our hosts were walking us to as we traversed the city, ending up at the lively and colourful Mercato Ritrovato farmers market.

Sitting snugly on market benches, we were treated to some amazing local foods, (wines and beers) all devoured ‘market’ style with fingers and bread! Red mullet, squid, anchovies and clams all hit the spot. This is a special place as the unused fresh produce is always given to the city’s not so well-off. We then strolled with a most delicious gelato to our next wine tasting!

Our much later supper was situated in the magnificent medieval Abbey of Monteveglio, overlooking staggering vistas and perfectly manicured vineyards as the sun went gently down. Our hosts at the family-run Trattoria del Borgo had created a beautiful table in their ancient restaurant as we were welcomed with plenty of Pignoletto, a surprise Sauvignon Blanc, Barbera and bonhomie by the vat full! Several courses were offered, my favourites being a green nettle tagliatelle, fried parmesan crust (eat it quickly!) stuffed courgettes and the exquisite Torta di Riso, a delicious rice cake.

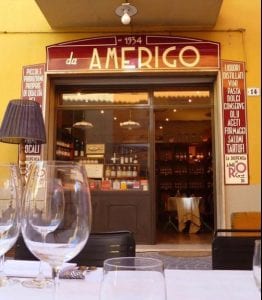

A light lunch in the wineries in Bologna usually comprises of antipasto by the table load! A mammoth tasting is often wolfed down with gusto with plenty of gentle frizzante. Not so with our last dinner together, as we were treated to one of the very best trattorias in the region – the Michelin-starred Trattoria Amerigo 1934 was right up our streets. Situated in the Bolognese hills, this is a restaurant of distinction. Sporting an amazing deli and enotica, we were settled in one of three (tiny) restaurants in the building. We were downstairs and saw the simple way that locals would sit cheek by jowl with destination diners.

A light lunch in the wineries in Bologna usually comprises of antipasto by the table load! A mammoth tasting is often wolfed down with gusto with plenty of gentle frizzante. Not so with our last dinner together, as we were treated to one of the very best trattorias in the region – the Michelin-starred Trattoria Amerigo 1934 was right up our streets. Situated in the Bolognese hills, this is a restaurant of distinction. Sporting an amazing deli and enotica, we were settled in one of three (tiny) restaurants in the building. We were downstairs and saw the simple way that locals would sit cheek by jowl with destination diners.

Our supper was hosted by the third-generation proprietor, Alberto Bettini, who deftly guided us through courses of exquisite local cuisine, cooked with understanding in the guise of the Slow Food Movement. Each dish was offered with (at least) one bottle of wine that he had hewn from his cellar. Outstanding dishes were hand chopped raw beef cubes with shaved white truffle, no-fill pasta with gentle lemon and crème fraîche sauce coating the pasta with elegance. Perfect Lasagne with rare local fungi (it had been raining for four weeks!) and a magnificent (steak) cut of deer, served pink to perfection.

The wines served ranged from old-vine frizzante to a bottle-aged Negretto. Dining here is the best experience imaginable – the combination of truly local dishes cooked with aplomb will stay with us for a very long time.

On behalf of the touring members of CWW to Colli Bolognese in June 2019, I would like to offer many thanks to the professionals involved and the manner in which the outstanding local dishes were brilliantly chosen at the outstanding restaurants on our all-too-short visit.

Thanks to Carla Capalbo for making this wonderful trip available to other Circle members.