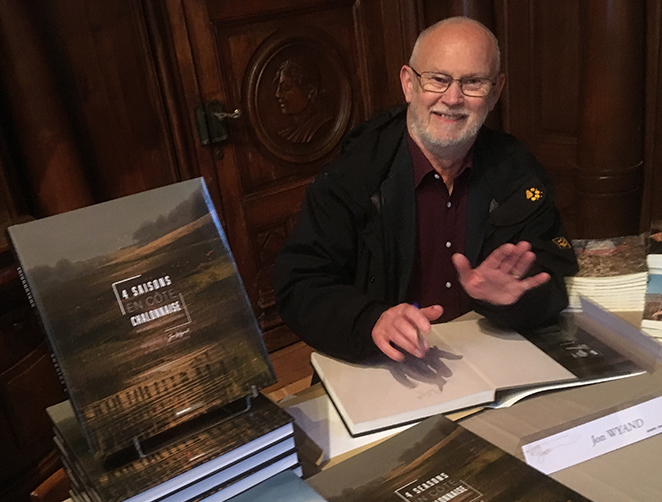

Jon Wyand is an award-winning photographer whose many works include his own two books, 4 seasons in Côte Chalonnaise and A year on Corton. In this interview, Amanda Barnes learns how it was his £1-a-night job that lured him into the world of wine and of his plans for the year to come.

What first brought you into the world of wine?

Well, it wasn’t drinking it! Alcohol was not a thing in our family. When I started work, I got a part-time job in a local pub for £1 a night in the late 60s. It was a great place to observe humanity from a nearly always safe distance. I seem to remember that we sold bottles of Grants of St James Côte de Beaune and Nuits St Georges in the off-licence but it was too early for wine by the glass.

When I started freelancing as a photographer, my first customer was a book packaging company called Jackson/Morley, in Soho, consisting of Michael Jackson as editor, with an interest in beer and whisky, and Bob Morley, who handled design and production. They later became Quarto Publishing, when Laurence Orbach came on board. Laurence was a wine enthusiast and was later responsible for the birth of World of Fine Wine.

My first two assignments were to illustrate The English Pub and The World Guide to Beer, whereby I came across a young Australian by the name of John Duval, in a Munich beer hall. He had just finished a grape harvest on the Rhine and told me over his stein of Spatenbrau that “beer was OK but wine was much more interesting”. It was many years later that I recognised him in a Penfolds ad.

Then followed The World Guide to Spirits and Liqueurs, and then Great Vineyards and Winemakers, which was edited by Serena Sutcliffe. I spent seven weeks covering France, Italy and Germany from the starting point of complete vinous ignorance. Of course, in seven weeks of such emersion you sank or swam and I returned home with ninety-seven and a half bottles of souvenirs that ensured my continued interest. It was another six years before I thought shooting wine was a viable career option. There were never photographic assignments, but just stock picture sales until Cephas came along and cleaned that up.

However, I heard about Wine Spectator and was put in touch with James Suckling and Tom Matthews in their London office in 1988. That was really the start and things grew from there. I have been lucky to taste some famous stuff but I was always focussed on the pictures. All the while I was moving from book illustration to corporate work and that is a very well paid but competitive area and as it gradually diminished, wine took over. Less money but more fun and I seemed good at it.

In 1999, a picture researcher advised me to restart my photo-library by specialising in one region rather than trying to compete with worldwide coverage. I chose Burgundy.

What are your favourite wine subjects to shoot?

The landscape, the people and the work are what I love and you have to learn what is going on. Patrick Eagar was a great wine photographer, when not earning his living being the best cricket photographer in the world by understanding the game inside out. People always assume wine photography is all about bottles in a studio. Personally, my interest photographically stops after bottling, I don’t do ‘lifestyle’, I’m too interested in authenticity and Burgundy is a pretty authentic place. I’m not interested in projecting a PR or advertising image that’s not authentic.

Wine is an amazingly photogenic subject but it’s too easy to shoot vineyards with blue skies and winemakers holding glasses and bottles. In 2010, I spent ten days shooting the harvest at Pontet-Canet. A wonderful 24/7 experience with a carte blanche and no brief. The following year I came up with the idea of ‘A year on Corton’ [which became the French publication Une année en Corton] and pitched it to Jean-Charles Le Bault de la Morinere at Bonneau du Martray. Discussions started with the Corton ODG and they canvassed for subscriptions among the growers. Burgundy moves slowly and I did not start shooting until 2013, when Glenat agreed to publish. Jasper Morris kindly contributed one of the specialists’ pages but the publisher wanted the book to be one-third text and the growers knew they had plenty to talk about, so a French writer was brought in. Sadly, the idea of an English edition did not interest the growers.

Burgundy is not the home of vanity publishing so I had a fairly free hand and the ODG continued to be pleased with the result. I learnt so much and three years later I was happy to be invited to do a similar sized project for the Côte Chalonnaise, after taking part in the annual Chalon-sur-Saône wine photography exhibition. A local publisher was chosen, along with a well-known local author for the few pages of text, and a very good relationship formed, giving me more control than Glénat had allowed. Fortunately, an English edition was produced but 1,000 copies were of no interest to the distributor Hachette and that led to another learning curve, just as Covid struck.

How has the pandemic presented different challenges to photographers? And do you see anything changing in the industry going forward?

Being based in the UK has been a problem. I’ve managed two four-day assignments in Champagne and a week in Burgundy since spring 2020. France and other wine producing countries all have a home-grown wine photography industry to cater for their needs and assignments have gone elsewhere, if indeed there were any to begin with.

Photographically, the future will turn around but my recent years of writing, carefully avoiding any fake expertise, have brought me clients in the UK, Norway and India.

More importantly as a photographer I’ve had the opportunities to find my own voice, which does not seem to compete with the rest. Let’s see if it has a future.

What are your plans for 2022? And are there any interesting projects you are working on?

As things open up, I look forward to a very varied life but I have greatly enjoyed the challenges of being involved with my own books over the last few years. However, when Une Année en Corton appeared on Amazon, my 90% contribution to the book was sadly not sufficient to see me listed as the author, only as contributor. Trusted others have encouraged me to dare to add my own words to my pictures. And I have begun, but I am no wine expert, no ‘influencer’. I’m hoping my photographic encounters with winemakers, plus 500 words, can be turned into a book one day, introducing wine drinkers to winemakers in a real wine world, devoid of scores and tasting notes – which can be equally as enlightening.