Author and wine writer Paul White has lived in several different corners of the world, from Oregon to New Zealand, and visited over 90 wine regions. In this interview he looks back on memorable wine experiences around the globe, as well as musing on the world of clay amphora in winemaking.

Tell us about your first experiences in wine?

I was born in a post-prohibition Des Moines, where alcohol was only sold from state-owned stores. To celebrate my 18th birthday, I sauntered up to the Iowa state liquor store and bought my first ‘legal’ bottle of wine, a Bordeaux white. It had a herd of cows on the label and, although as sour as it was lean, it made me feel very sophisticated. It also brought a smile to my face and started a lifelong love-hate affair with Sauvignon Blanc.

Born a year and a mile away from Bill Bryson, like other curious Iowans, I left to explore the world outside. Oregon was the next stop, arriving smack dab in the middle of its revolutionary Pinot Noir Pioneer period. All that orientated me toward cool climate, high acid wines. Although I adopted Oregon’s typical ‘don’t Californicate us’ attitude to wine, nevertheless, I drank a lot of trendy Californian varietals, including Mondavi’s groundbreaking Fumé Blancs, Cabs and Chardonnays. The 1970s were a heady time, when American wines came of age.

Moving to the United Kingdom in the 1980s, my attention turned toward a more serious study of the European ‘Classics’. I lucked out, landing a doctorate slot at Oxford, and an even luckier slot captaining the university’s Blind Wine Tasting Team for several years. Learning to taste for terroir, climate and grape types from the inside out of a glass, I quickly realised there was no better place on earth to study wine than Oxford [with its] daily trade tastings, 36 college cellars and the Tasting Team. I must admit my DPhil took a couple more years to complete than it should have done.

I liked the Brits because they drank wine from everywhere and were able to tell you why, in detail. Equally important, I started judging for IWC around 87-88 (yearly up to 2005) and learned so much judging alongside ‘old school’ merchants and MWs. It was around then that the newest wave of New World ‘Sunshine in a Glass’ wines appeared from Down Under. Aussies first in 1986, quickly followed by mind blowing Kiwi Sauvignon. And then I judged a revelatory Rippon Pinot Noir 1990 or 91 at IWC.

When did you move to New Zealand?

Doctorate in hand, having done American and European wine, I relocated to New Zealand in 1993, chasing Central Otago’s Pinot Noir potential, also intent on checking out the whole Australasian wine scene. I was pretty much the first Yank on the ground there, managing to visit most regions repeatedly over the years. I wrote columns for NZ’s two main newspapers and Australia’s leading wine mag. It was a fun time sharing in the discovery of what Kiwis were capable of creating. Early Oregon, all over again.

In the 2000s, I shifted back toward a European focus, writing articles or columns for World of Fine Wine, Italy’s Slow Food/Slow Wine, Portugal’s Essencia do Vinhos and other publications. Slow food was especially influential.

Around 2005, I became actively involved in SF’s Vigneron d’Europe 2005, Vignaioli e Vignerons 2009 and Terra Madre congresses. These protest movements changed EU viticulture policy away from industrial subsidies towards small producers and tightened up organic rules that replaced proposed, heavily greenwashed, guidelines. Since then, I’ve mainly focused on little guys, underdogs, endangered grapes and wine cultures, and under-known regions and producers. Talha culture is straight out of Terra Madre’s focus on reversing cultural extinction.

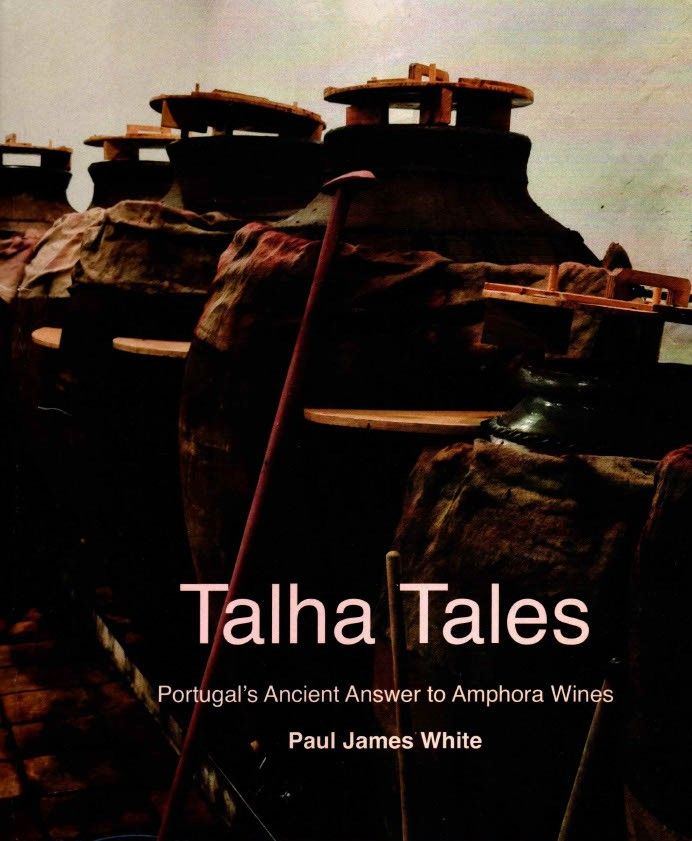

You’ve just published your book on the talha wines of Alentejo after several years of research. What kept you particularly engaged with the wines there?

It’s most specifically the talha wines that were of interest. I’d not been a fan of many Alentejo wines because they were so Parkerized or Australian-like – over oaked, over extracted, over alcoholic, identi-kit, internationalist, modernist – as has been too much of Douro unfortunately.

The talha wines were serious outliers. Remarkably pure, high acid wines at 12% alcohol. Surrounded by regions making reds at 14-15%, it didn’t make sense. Something unique was going on there. On top of being the only continuation of Roman clay pot technology, the wines were genuinely from a place and always interesting for their typicity.

I’ve long hated what Parkerization, internationalist and ‘modernism’ pressures have done to Portugal’s traditional styles and the destruction of its autochthonous, old vines. Talha were clearly on the brink, so it was hard to not get involved in telling their story. The unforeseen development came after traditional talha styles were secured. The same ancient technology was managing to spin out entirely new, highly innovative ‘post-modern’ wine styles as well.

Are you a fan of other amphora wines? Or is it particularly the talha wines? And do you see the talha having a future in regions outside of Alentejo?

I kind of wandered into the whole amphora wine movement by accident, and like quicksand, it pulled me in ever deeper. In a sense the attraction was a logical extension of my previous musical career, which was essentially about musical terroir. My doctorate was in history of musical technology. I used to build and play 17th, 18th and 19th century bassoons – all pre-industrially handmade. These were banded together with other instruments in ‘period’ orchestras, specific to what Vivaldi, Bach, Mozart and Beethoven each would have heard in their day and specifically composed for. The resultant performances proved superior to modern instruments playing the same compositions, which is why I’ve long believed that historic technology can hold its own against modern tech. It is capable of creating either comparable, better or, at the very least, simply different results.

I first ran into one of Josko Gravner’s amphora disciples in Istria in the mid-2000s. I’d found Gravner’s wines interesting and enjoyable for a glass or two, but not always pleasurable. Also, I didn’t get why Gravner was trying to make Roman-era wines by adopting below ground Georgian qvevri, a totally different clay pot technology, process and style.

A few years later, on a Slow Food assignment, I tasted Luigi Tecci’s Aglianicos in Campania made in both Greek and Roman, above ground, Dolia-style pots. He was theory driven, reading ancient texts and driven by gut instincts and trial and error, intently focused on figuring out what may have been. Both wines were quite good, drinkable and surprisingly modern in style. They were the antithesis of Gravner’s qvevri, orange wine approach.

Eventually, I caught wind of a handful of dirt-poor villagers in Alentejo still making wine in pots, like the Romans had. I begged my way in to check out this ‘living history’ and in 2012 Alentejo’s CVR (Comissão Vitivinícola Regional) put together a wonderful discovery tour for me. Annual production was down to 700 litres by then and clearly on the edge.

Thereafter, I got hooked on helping the talha producers stave off extinction. A decade on and that culture is thriving, not only producing classical styles but also using clay pot fermentation and maturation to create entirely new styles that can compete with anything produced in oak or stainless steel. It really has been forward through the past.

Ironically, it was talha that drove me to visit Georgian qvevri and Armenian karas winemakers to understand where they all fit together, or didn’t. As for talha’s influence outside? It’s already happening but there’s more to come. Armenia’s nearly extinct karas production, for example, has looked to talha culture’s restoration for inspiration on how to restore their own.

The ‘amphora’ movement has been burbling stealthily underground for a couple of decades now. Luckily, up until the last couple of years, I’ve been the only journalist covering the annual ‘ground zero’ events that have helped bring this diverse movement together and codify how the technology has been and will be used in future.

In 2014, I missed the first gathering of Florence’s biennial Terracotta Wine. This was mainly producers using local Artenova pots, who had begun resupplying above-ground dolium throughout Europe. The seminar cum wine fair was mostly made up of Italians who were rejecting Gravner’s qvevri styles, fleshed out by a few French, Slovenians, Georgians and Armenians. None of them were aware of Alentejo’s continuous Roman tradition, while similarly the Alentejan’s assumed they were completely alone. I contacted the Terracotta Wines organization to see if we could bring them all together.

Terracotta Wine 2016 invited in nine talha producers for the first time, with further expansion across Europe to South Africa and Australia – which has over 120 pots brewing – and Oregon. They’ve all gotten on like a house on fire since. Alentejo’s Heredade do Rocim organized the first annual Amphora Wine Day in 2018, creating a second forum for amphora producers to meet and for punters to taste the current state-of-the-art, terracotta-made wine.

How talha have reshaped the amphora movement remains an ongoing story. The unbroken chain of Roman technology – in fact, it probably goes back to before the Phoenicians – and the continuous oral history continues to bring a wealth of experience to all forms of amphora wine. The wines have much shorter periods of skin contact than Georgian qvevri styles. Talha are much closer to modern wine styles, sharing barrel fermentation qualities, but are more purely fruited and untainted by oak’s aromas, flavours and tannins.

The recent discovery of 19th century clay-made barrels in central talha country has created a whole new genre of clay-aged wine that I know has caught the attention of several American wine producers. Rocim and Quinta de Pigarca have pioneered this with great results. Still early days, it’s bound to grow in importance. I reckon pots will become as ubiquitous as barrels in future.

Another completely overlooked potential influence is the Alentejan tradition of producing and serving wine straight from talha to tables inside restaurants. This has huge potential globally, mirroring brew pubs. Anyone who has visited the few remaining restaurants in Alentejo and seen their magnificent line-up of monumental old pots will understand the grandeur they bring to a space.

You’ve lived in and travelled to many different wine regions around the world. Are there any, beyond Portugal, that are particularly close to your heart, and why?

Yes, I’m lucky to have visited over 90 wine regions in 30 countries on six continents. I like wines from all over. My tastes are quite promiscuous. Experiencing new grapes and styles are long standing passions. Italy and Portugal are always stimulating for their wealth of grape varieties and styles. Dão and Madeira have a special place in my heart and I’ve rarely been disappointed by their longevity and complexity.

I like wines that age well and am a ‘better red than dead’ kind of person. Where Oregon shaped me into a Pinot guy, I’ve evolved into preferring Nebbiolo, Nerello Mascalese and Aglianico and, eventually, on to Areni, Alfrocheiro and Moreto. All share similar aromatic intensity and transparency, but edgier tannins. Pinot for adults.

Of course, Loire, Burgundy, Rioja, Alsace, Austria and Oregon continue to produce interesting classics that I’ll never turn down, unfortunately so many are beyond the means of us mortals these days. Fine wine moved beyond France decades ago, it’s just people with loads of money that haven’t figured that out yet.

What will you be looking forward to in 2023?

I’m halfway through a book on Dão wine and another on Slovenia. Trips to Portuguese regions are on the cards. I’m hoping to do follow up tours of Slovenia, Armenia, Madeira and Georgia this year. I’d love to explore clay pot wines in the war zone regions of South Ossetia, northern Turkey and Azerbaijan. I’m hoping to return to the homestead in Wellington, New Zealand, with a stopover in Oregon. It’s looking to be a good year.