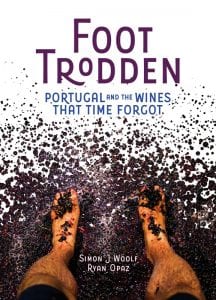

Exploring the foot trodden and handmade wines of Portugal, Simon J Woolf and Ryan Opaz’s new book, Foot Trodden, is being funded and brought to life through a Kickstarter campaign which is live now. In this extract, Simon explores the wines of the Alentejo region in southern Portugal, and, in particular, those that are made in talha clay pots.

The best way to understand Alentejo’s strong sense of community is via a clay pot. Locally known as talha, these large, free-standing clay amphorae have been a fixture of village life since Romans introduced the idea over 2,000 years ago.

The wine produced in the region’s small cellars (adegas) is shared copiously with friends and family, straight from the talha. It’s almost never bottled, although locals will purchase and take out a litre or so in whatever plastic receptacle they have at hand. As winemaker Ricardo Santos explains, when you go to drink wine in a friend’s cellar, payment is not expected – it would be the height of bad manners to suggest that money changed hands. But they know you’ve got their back, either in this life or the next.

Traditions of clay

Ricardo now lives near Lisbon, but he grew up in the small village of Vila Alva, about 200km east of Lisbon. “There’s a talha behind every door” is the claim in Vila Alva – and in other nearby villages such as Cuba, Vidigueira and Vila de Frades. It seems hard to believe, but it’s true. The owner of one of the two cafes in Vila Alva walks across the street and rolls up the shutter of his garage to reveal a large talha (taller than a person) tucked away behind his car. Sadly it’s no longer in use. But just up the street, Ricardo bumps into another friend whose garden shed turns out to house three small clay vessels, all full to the brim with wine.

The regional tradition here has barely changed in centuries. Grapes are foot trodden and crushed on the floor in the middle of the adega, with a ladrão or ‘thief’ buried right underneath to catch the juice. The crush then goes into the talha, with a small layer of the grape stems at the bottom. This provides an all important natural filter, through which the wine will eventually drain.

The wine ferments spontaneously with ambient yeasts in the open vessel, with a cloud of CO2 protecting it from oxidation, and a little help from the winemaker who breaks up the cap of skins every now and again. If this is not done, the pressure from fermentation can rocket up and potentially cause the talha to explode.

Talhas also have their own built-in temperature regulation system. Traditionally, cold water is sprayed over the thick stone braiding around the neck of the talha, which distributes it evenly over the entire body of the vessel. It sounds primitive, but it’s remarkably efficient. Fermentation temperatures can be reduced from a dangerously-high 40C (where there’s a risk that the wine ends up tasting stewed or cooked, and loses its fruit character) to a much more reasonable 20C.

Once fermentation has finished, the talha will be sealed from the air with a paper-thin layer of olive oil. Talha wine expert Arlindo ‘professor’ Maria Ruivo, says that the best wines were always sealed with the best olive oil, and that sometimes you could taste a “beautiful whisper” of the oil in the finished wine. This wasn’t seen as a bad thing. Most winemakers also loosely cover the top of the talha with anything from a black bin-liner (functional) to a fancy embroidered cloth (Instagram and tourist friendly), to keep the flies out.

The wine isn’t touched again until o dia de São Martinho (St. Martin’s Day, which occurs on the Sunday closest to November 11th). From this day on, it’s deemed ready to drink – straight from the clay. The winemaker will insert a wooden tap (the batoque) into the bunghole at the bottom of the talha, and let the wine drain drip by drip into a strategically placed bucket or bowl.

The slow drip… drip… drip… sound emanates happily from all the region’s small adegas at this time of year. Patience is required, as the wine filters at a glacial pace through the layer of grape stems that have sat at the bottom of the talha for the last 60 days or so. If it’s the branco you’re about to taste, the colour will be a beautifully translucent amber. Tinto or petroleiro (a red and white petrol-coloured mix, otherwise known in Portugal as palhete) span the gamut from light ruby to deep purple.

Tasting, as the locals call it (the dividing line between tasting and drinking can be delightfully fluid), takes place throughout the winter and until the wine runs out, which might be January or February depending on how thirsty the villagers happen to be. Adegas at this time of year morph into ad hoc bars, with small tables covered in gingham tablecloths. Anyone is free to stop by and have a glass or two. The glasses play to the idea that you are tasting – they’re small, stemless and straight, looking more like a shot glass than anything else.

Visit one of Vila Alva’s larger cellars such as Adega Manual Fernando, and the scene looks like something from the last century. A group of old-timers sit in a dingy corner of the cellar, all wearing their traditional flat caps as they toast and chat. A younger group holds court out front, and one man grills sausages on the small open hearth. This is standard procedure when visiting your friend’s cellar – bring something tasty to share. They’re providing the wine, your responsibility is the snacks.

Zé is the host and winemaker, and he’s being kept busy filling glasses as more guests arrive. All around the cellar, the talhas ceremoniously drip their precious contents into plastic trays and buckets. It could be a wildly popular tavern – except that there is no tab, and no money changing hands.

It’s now Sunday lunchtime in Vila Alva, and the adegas buzz with life as people stroll back from the village church eager to taste the new wine and chit-chat. An unmarked door on the Largo da Fonte lies open. The small clay fragment of a talha mounted on the wall outside is the only clue as to what lies within. This is Adega Marco “do Panoias”, and although it’s small and modest, this cellar holds treasure – the oldest surviving talha in the village, with a just-about-visible date of 1679 scratched into the fired clay on its neck. The squat vessel, also etched with a rather qabalistic-looking symbol representing its maker, is no museum piece. It’s full to the brim with a thirst quenching, delicious red wine, made from a typical field blend of varieties such as Trincadeira and Alicante Bouschet.

Just across the square, Izalindo Marques has opened up his tiny adega, with six talhas squeezed chaotically around unused chairs and other junk that presumably doesn’t fit into his house. He lines up shot glasses of his spicy and tannic talha branco on a rough trestle table which takes up all the remaining floorspace. Bunches of drying grapes are strung from the ceiling, ready to snack on during the winter. The walls are lined with plastic flagons, ready to share the wine with thirsty friends.

Revitalising the adega

Daniel Parreira is a young civil engineer who lives and works in Lisbon. He’s urbane and speaks perfect English, however Parreira grew up not in the city but in Vila Alva. When he was a boy, Parreira thought that all wine came out of a talha – he’d seen his grandfather, his dad, uncle and all their friends serving wine straight from the clay vessels. The illusion was only shattered when he turned 15.

His grandfather, Daniel António Tabaquinho dos Santos, was known as Mestre Daniel, as he was a carpenter in addition to making wine. His son (Daniel’s father) continued to make wine at Adega Mestre Daniel, but ceased production in the 1990s. Daniel the younger still remembers the cellar being in active use though. More than a decade later, he and his sister decided to restore the adega and turn it into a museum to the area’s winemaking tradition. They also used the handsome space, with its typical lime-washed walls and wood-trussed ceiling, to host parties and other events. The cellar still had its quotient of 26 talhas lining the walls. These venerable vessels, many over a century old, silently watched over the proceedings as they sat empty and unused.

Something was missing. The space just didn’t feel the same without the smells and the sounds of wine fermenting. Ricardo Santos is a childhood friend of Daniel’s, and his dad used to work for Daniel’s grandfather, in the talha cellar. Ricardo since developed his career as a winemaker consulting for a number of wineries in the region. He suggested the idea of bringing the cellar back into production. It would be a homage to Daniel’s grandfather. His grandmother, still alive although very old and infirm, was delighted.

Daniel and Ricardo had to jump through some legal hoops, but once the bureaucratic demands were satisfied, they were able to start active production again from 2018 (they now bottle some wines under the brand XXVI Talhas). But Daniel didn’t just want to produce wine – he wanted visitors to be able to understand the history and the culture behind the wine.

He painstakingly researched and designed a map of Vila Alva which shows all of its historic adegas. By the 1950s, this village with its 800 or so residents had 72 known cellars that were all in use. Daniel only counted adegas that had at least three talhas. Otherwise, he’d be counting just about every house in the village.

Only eight of these adegas are still active in Vila Alva. A further 14 cellars still exist, but are dormant. The saddest statistic is the 50 cellars that have completely disappeared – their talhas sold off, and the buildings bulldozed or converted to more mundane uses. A century ago, there were more talhas in the village than residents (Daniel calculates 1,046 in total), yet today only 200 have endured. The remainder were sold off to become garden ornaments, or to be installed in the centre of roundabouts – or worse still, ground up to become part of the road surface.

Foot Trodden: Portugal and the wines that time forgot by Simon J Woolf and Ryan Opaz is currently live on Kickstarter. In order to support Simon and Ryan and help the book come to life, you can find out more online and support the campaign through their Kickstarter page: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/simonjwoolf/foot-trodden-portugal-and-the-wines-that-time-forgot

Foot Trodden: Portugal and the wines that time forgot by Simon J Woolf and Ryan Opaz is currently live on Kickstarter. In order to support Simon and Ryan and help the book come to life, you can find out more online and support the campaign through their Kickstarter page: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/simonjwoolf/foot-trodden-portugal-and-the-wines-that-time-forgot