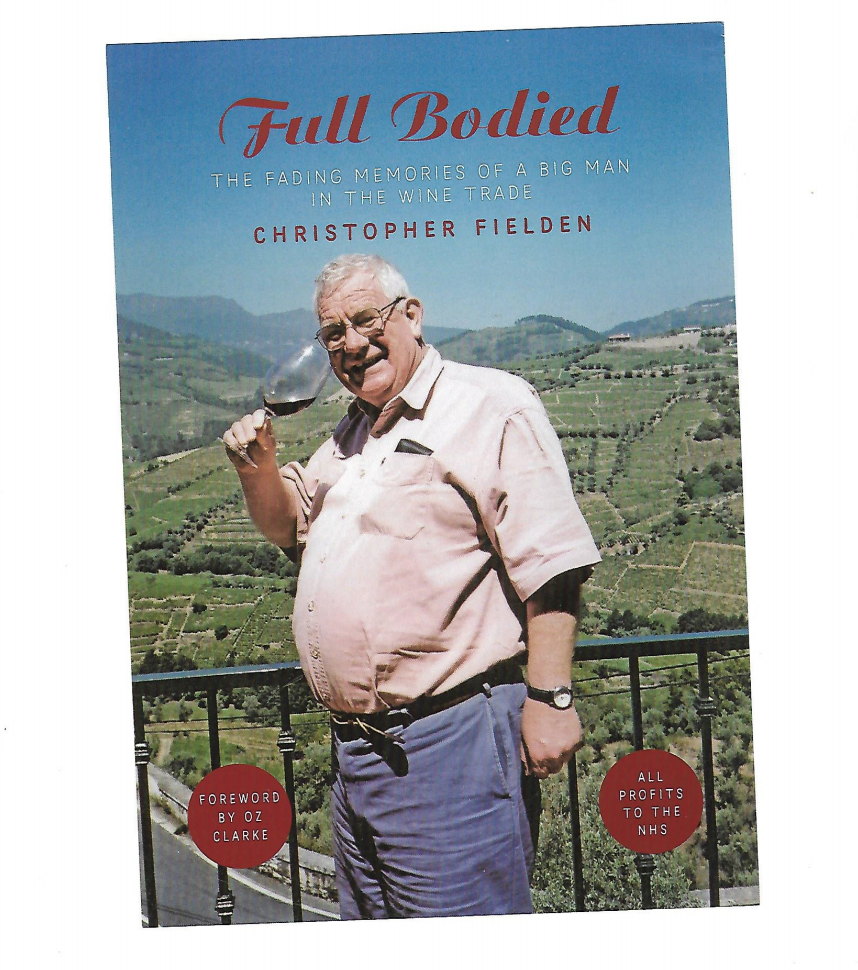

Christopher Fielden spent lockdown earlier this year penning his memoirs, Full Bodied: The faded memories of a big man in the wine trade, which Amanda Barnes reviews this month. We also publish an entertaining extract from the book as Christopher gets to grips with the Albanian wine market.

Christopher Fielden has incredible stories that you can truly relish in with him in his newest book, Full Bodied. From being stranded in Ibiza with Mick Jagger and posing as his catering manager to procuring a smuggler’s license and introducing Irish whisky to Paraguay, they are often so fantastic that this feels more like fiction. But there is nothing fictional about his fascinating memoir which offers a delightfully personal tour of many years of his life in the wine trade and he also guides the reader through some of the important periods of the wine industry that accompanied him.

Starting his career in 1958, he has witnessed and been part of some pivotal changes in the industry as a buyer, supplier, importer and writer among other roles, even managing a bottling line in England at one stage when ‘there was a very relaxed attitude towards the labelling of wine’. Christopher indulges the reader in some of the secrets and tricks of the trade at the time, reporting on scandals and large errors, which are often both shocking and entertaining.

His early career by no means followed the conventional route. From importing Albanian wine to blending Japanese whisky, what is perhaps most remarkable and engaging about Christopher’s memoir is quite how much and quite how diverse his experience has been around the drinks world. That’s not to say he lacks experience in some of the most classic wine regions of the world — he is also considered rather an expert on Burgundy (where he lived for some time), Spain and South America, and was one of the early advocates for wines from Napa and Australia.

There are also some deeply personal accounts of his life including family decisions, a few driving debacles and even medical diagnoses (the most cruelly chucklesome of which is when his doctor made him abstain from alcohol for a whole year to later find out that his emergency liver problem was, in fact, a misdiagnosis and nothing more than excessive wind).

Although most of the chapters are ordered chronologically and by important appointments and destinations in his life, the later chapters also detail his writing career, work in education and some memories of his time in the Circle and other associations, and pay tribute to all the women who have helped him in his career.

Full Bodied is a rather juicy read indeed. From boozy lunches to near-arrests and near-deportations, there are plenty of engaging stories in Christopher’s memoir to give you an idea of just how full his life in wine has been. Entertaining, candid and good fun.

– Amanda Barnes

You can contact Christopher [email protected] to purchase a copy of Full Bodied. All proceeds of which will go towards the NHS.

Albania: An extract from Full Bodied

Looking back in hindsight there were two other entrepreneurial moves we made that proved to be disastrous. The first of these was to involve ourselves in Albanian wine. One of our salesmen had some form of dubious relationship with the Marxist owner of a wool shop in Chorlton-cum-Hardy. Somehow, she had heard that the Albanians were keen to sell their wine in Britain. On the face of it, that appeared to be a project of some interest. One of the top-selling wines here at the time was Lutomer Riesling from Jugoslavia. (This was not the Riesling as we know it now, but rather the Central European Laski Riesling or Grasevina.) Here was the possibility to break into the national market.

At the time Albania was the pariah country of Europe. For years it had been bankrolled by Russia, who valued it as a useful foothold on the Mediterranean, but its individualistic leader Enver Hoxha who had deposed King Zog in 1946, now dismissed Soviet Communism as Kruschevite revisionism and was left with just China as an ally in the world. The British maintained no diplomatic relationship with the country, as there was some dispute as to who was responsible for the destruction by mines of two British destroyers in the Straits of Corfu. The challenge therefore of importing Albanian wines was a considerable one, but one that we felt we could overcome.

Access to the country was not easy, as there were only a very limited number of flights there each week. Despite all this, Roger Duxbury and I decided to proceed. The nearest Albanian embassy was in Paris, so we contacted them to arrange visas. The plan was to pick them up there on morning one, then fly on to Belgrade where we would spend the night and then fly to Tirana on morning two.

Matters did not go according to plan. We flew to Paris and went to the Albanian Embassy at the rue de la Pompe. Whilst they had heard of us, they had, for some reason, prepared visas in two totally different names. “Not to worry,” they said. “If you fly to Belgrade, you can pick up the visas in the right names there and fly on to Tirana on the weekly flight later that day.” Accordingly, we took the Jugoslav Airlines flight to Belgrade that evening. The following morning we presented ourselves at the Albanian embassy there. “Yes, we do have your visas,” they said, “but they will not be ready until this afternoon.” “That is all very well,” we replied “but this means that we will miss the only flight this week to Tirana.” “Not to worry,” they said, “If you fly to Titograd (now Podgorice, the capital of Montenegro, on the border with Albania) there is a bus from there which leaves for Tirana at ten tomorrow morning.”

After returning to collect our visas later in the day, we took the flight into the unknown early that evening. Again it was a Jugoslav Airlines flight and, fortunately for us, one of the hostesses had been on the flight from Paris the previous day and recognised us. She asked us what we were doing, flying to Titograd and we explained what had happened and that we had no idea as to where we might spend the night. Luckily she was able to point us in the right direction and we found a suitable hotel.

The following morning at nine o’clock, we presented ourselves at reception, with our bags packed, to ask from where the bus for Tirana would leave. The answer came that on this occasion it had left an hour earlier. By this time we had come to the conclusion that fate was working against us. (In hindsight, in the long run, it might have been better if it had continued to do so.) In desperation, we went to the airline office to see how we might be able to get back to Manchester. Once again, we met a very helpful girl, who told us not to despair. If we were to go to the wasteland behind the post office at midday, there should be some transport leaving for Albania. We duly did as instructed and there was a pickup truck laden with mail bags, a driver and a shotgun armed guard. We travelled sitting on top of the bags, with the guard, who fortunately had spent part of his life in Chicago and spoke reasonable English.

Somehow, news of our route into the country had reached the capital and we were met at the frontier by a car and a representative from the export ministry. He asked us if we would like to drive straight on to the capital, some three hours’ journey, or spend the night in the local hotel. On having a look at the latter, we decided on the former.

The Hotel Dajti was on the main square in Tirana. It had an imposing reception and the rooms could be described as adequate, but certainly not luxurious. In the lobby, there was a telex machine endlessly churning out the local version of the world events as interpreted by the national news agency. Free copies of the speeches of Enver Hoxha were available, translated into English, as was a history of the country. At seven o’clock each morning, everyone was out on the street doing star jumps and similar athletic exercises. This reminded me of some of my most loathed moments at school. The food consisted of mince and root vegetables. When we asked our hosts whether there was a restaurant where we could take them for a meal, they said the hotel was the only place.

All the Albanians we met were very friendly. We were taken to the Red Star Co-operative Cellar in Durres where we were lavishly, liquidly entertained, not just with wine but also with raki and fruit liqueurs. In the event, we ordered some casks of Riesling, Cabernet and also a local varietal, Mavrud, for shipment for bottling in England. We also jointly agreed on a brand name for the wines: Skanderbeg, a national hero.

As our flights were only once a week, we found the following four days somewhat difficult to fill in, so we also visited the mountain town of Krujë, 12 miles or so from Tirana. This was a centre of carpet making, so Roger, who had a side-line interest in carpet distribution in England, ordered some samples of carpets and kilims. It was agreed that I should return to inspect the wines before shipment, two or three months later.

Our return journey involved a night’s stay in Budapest. After the austerity of Albania, an evening’s entertainment at Madam Arizona’s Bar came in complete contrast. The following morning, I found Roger asleep, fully dressed in an empty bath!

There were no problems with my second visit. This time, it meant collecting the visa in Rome and flying on, with Alitalia, via Bari. In the meantime, as agreed, we paid for the wine in advance and said that we would arrange shipment with our forwarding agents. “Do not worry”, they said, “We will put it on one of our ships and deliver it to England.” We agreed, but most unfortunately, the ship did not set sail for another three months and, in the meantime, the casks of wine had been sitting outside in the sun, awaiting collection.

Originally, we were told that the ship would dock in Dover, but in the event, it arrived at Tilbury on New Year’s Eve. Ann and I arranged to visit them in port the following day with a reporter from The Daily Telegraph, as this was the first Albanian boat to arrive here for 40 years. We were also accompanied by a representative of the Marxist-Leninist Association of Great Britain, an optician from Ilford. When we arrived at the dock gates, the security guard said he was very pleased to see us for, as soon as the boat had arrived the previous evening, the crew had immediately begun to celebrate New Year’s Eve and no one had been able to make contact with them since.

Once on board, we were made very welcome and, under the eagle eye of the boat’s political commissar, numerous toasts were made in raki, pledging eternal friendship between the two countries.

In a bid to stir up some interest, we ran a series of cryptic ads. In the personal column of The Times, something like:

Substantial liquid assets from

Eastern Europe are now available.

Interested parties should reply to

Box…

Whilst we received some very interesting replies, none of them led to any sales of our wine.

Because the boat had docked at Tilbury, the casks had to be shipped by barge up the Thames to London, before they could be trucked to the bottlers in Liverpool. As a result of the delays before shipment the wines had suffered substantially and in no way resembled those we had ordered and which I had approved. Of the three, the Mavrud was the only one which bore any resemblance to what we expected. The Cabernet had lost most of its colour so we decided that we could only sell it as Cabernet Rosé. The Riesling was totally oxidised and we sold it in bulk for almost nothing to the bottler. He, I believe, blended it off and it finally made its appearance on the market under the guise of Cyprus sherry.

The Albanians were keen to sell us more wine, but we said, quite untruthfully, that the British government had told us that they would not release more money to us unless the Albanians were prepared to buy some British goods. What they needed. they said, were razor blades and fertilisers. We went to the producers of these and so I set out for Albania once again, armed with export prices and samples.

After some days of haggling, our discussions came to nothing. However, they would not give me the exit permit to leave the country so instead they installed me in the Hotel Adriatika in Durres. This had been built by the Russians as a grandiose resort hotel, when the country was in the Soviet bloc, where its role was to provide Mediterranean sunshine for the leaders, as well as pens for Soviet submarines. It was on a wonderful beach, the far end of which was blocked off for the use of the President’s holiday home. Sadly, the hotel had never been able to fulfil the role for which it had been built and when I stayed there, I was the only resident. The manager used to come along at six o’clock each evening and ask me to go to bed as he wished to close everything up. Fortunately, after two extra days in the country, my hosts relented and I was free to leave Albania never, so far, to return.

The story does have a sequel. Some weeks later, I was sitting in my office, when I received a telephone call from a major in the Ministry of Defence. Could he come and see me? As, at the time, we were supplying the officers’ mess at the local army base, where there had been some stock disappearing, I thought that it would be about this, so I suggested that he came to my office. He said that he preferred that we should meet somewhere else, so I suggested a local pub. When we met, he said that it had been noticed that I had visited Albania on three separate occasions, would I mind telling him why this was? I explained that I had been to buy wine and this seemed to satisfy him, but he said would I mind contacting him when I went again, as he might have something for me to do. I have frequently told this story in the hope that I might be considered a poor security risk and not a satisfactory James Bond replacement.

– Christopher Fielden