Wink Lorch tastes and tours through the Criolla grape varieties and wine regions of South America during Amanda Barnes’ Let’s talk about Criolla webinar earlier this year.

There was something intoxicating about this hour, and it wasn’t only that I was one of the lucky ones to receive three wines to taste.

“Crrree-oy-ya” intoned Amanda, a fluent South American Spanish speaker, who really knows how to roll her ‘r’s having lived for a decade in Argentina (until becoming stuck in Europe due to Covid…). Her confidence in her subject meant that I was drawn in immediately to her stories, which stretched from the arrival of Criolla vines with Columbus and other explorers of South America to today’s welcome revival of these old vines of South America. And by the end of this session, I felt that Amanda should have a personal descriptor: ‘Criolla Champion’.

Amanda introduces Criolla in her sumptuous new self-published book, The South American Wine Guide, (see the review by Tamlyn Currin) with the following useful explanation:

“The Spanish term Criolla is used to refer to people, cultures, and animal and plant species that were born in the Americas of mixed Spanish and native descent. And the great family tree of Criolla grape varieties is named for that reason.” She explained to us that the word Creole, as in the cuisine from the south-eastern states of the US, comes from this same root.

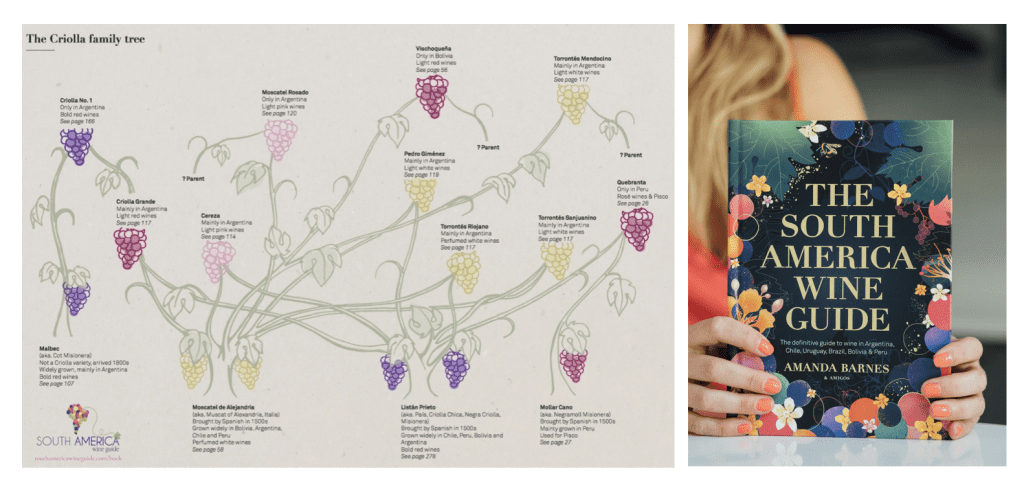

The word Criolla can be confusing as it may be singular referring to one of several grape varieties brought over from Spain or their descendants, or plural describing the several varieties of the great Criolla family. In Amanda’s book you will find a useful family tree and this indicates the descendants of the two main varieties, the black Listán Pietro and the white Moscatel de Alejandria (yes, the same as Muscat of Alexandria). Among this family are some new generation crossings with Malbec, Cabernet or Chardonnay, for example, but the Criolla varieties most of us know best and which are most available on the market are Torrontés from Argentina and País from Chile.

Seriously interesting are the great quantity of old vines in South America. Amanda explained that whereas Australia had done impressive work on classifying their old vines and dubbing those 70 years old or more as ‘survivor vines’, the figures from South America are even greater. Australia declares 5,750 survivor vines; South Africa has 3,000 or more over 35 years old; but Argentina has at least 7,400 and Chile more than 15,000 vines over 70 years old and many of these are well over 100 years old, even as much as 200 years old.

Following this introduction Amanda continued to describe Criolla’s history and current status for each of the main South American winegrowing countries on the west side (Brazil and Uruguay on the east do not have notable Criolla plantations). What follows is but a summary of highlights including comments on the three wines tasted:

PERU

The real birthplace of the commercial wine industry in South America, Peru still has a big grape growing industry, particularly for making the spirit Pisco (much from Criolla varieties) and for table grapes. However there has been a renaissance in making Criolla wines, some using traditional and natural winemaking methods including use of their own version of amphoras. It was encouraging and mouth-watering to hear about the top restaurants in Lima and that it’s the sommeliers who are driving this renaissance. There are seven main Pisco varieties, which are quite varied in style and all are now also used for wine.

BOLIVIA

Here the wine industry developed to provide wine for the huge influx of European people working in the Potosi silver mine from the 16th century onwards. The most exciting Criolla variety in Bolivia is the Moscatel de Alejandria, one of the first varieties brought from Spain – often it is still grown as the Jesuits did, using trees as a training system, up and around pink peppercorn and other herbal trees – the trees appear to add something herbal and complex to the typical floral aromas you would expect. Among other Criolla varieties, Vischoqueña is a purely Bolivian variety and produces a delicious light-coloured but high acid, tannic red, likened sometimes to Nebbiolo or Pinot Noir and we should see this on export markets soon.

ARGENTINA

Referred to by Amanda as the ‘titan of the wine world’, Argentina retains its position as the 5th biggest wine producer. Criolla grape vines have proliferated in all the wine regions from north to south, in particular because they are hardy enough to handle drought and many are hundreds of years old. Torrontés is the most important in terms of reputation in Argentina and nearly 10,000ha are grown of the three sub-varieties, named after the regions where they first appeared. The Torrontés Riojana is by far the most important and grown across the wine regions; then there is the less aromatic Sanjuanino and finally the lesser-quality Mendocino – although it originated in Mendoza, most vines grown there are Riojana. Torrontés Riojana gives typical exotic floral and fruit notes, and it was winemaker Susana Balbo, originally based in Salta in the north, who is most credited with developing the modern, fresh cool fermentation expression of the variety in the 1990s. What is particularly interesting is how the versatility of Torrontés has emerged in terms of winemaking and flavour profiles – various oaked styles are made and there is a growing trend for orange wines.

The CHAKANA Estate Selection Torrontes, Uco Valley, Mendoza 2020 tasted was made with a little oak ageing, which it supported well and served to enhance rather than detract from the tangy, juicy and exotic fruit palate. Tasting it again later, I found that it was one of those whites that show such an exotic aroma (stewed pears) that if you didn’t know better you would expect the palate to be sweet, yet it is bone dry with the freshness only high altitude gives and softness from the warm climate. Amanda said it went well with Asian, spicy foods or local cheeses and noted that today you can see really marked differences in Torrontés expressions across the Argentinean wine regions.

There is a plethora of Criolla varieties in Argentina, grown in substantial quantities, but the second wine we tasted was from Criolla Chica, of which there is just 349 hectares. CATENA La Marchigiana, Criolla, Mendoza 2018 was made in Rivadavia in East Mendoza, an historical part of Mendoza, which as a warmer, comparatively lower altitude region has been overlooked recently. Amanda welcomes the return of interest in the many very old vines grown here, often by farmers from families going back generations. This Catena wine was made using artisanal methods in 200 year old clay pots with no added sulphites. It shows a real softness and earthiness (it reminded me to some extent of a good Jura Poulsard) and was light and so eminently drinkable. Amanda suggested an Argentine-style, very meaty chorizo as an accompaniment.

CHILE

South America’s second biggest wine growing country also has many different varieties of Criolla growing from north to south including many used for Pisco production. Moscatel de Alejandria and Criolla Grande are grown near the border with Peru, where some are still made into sweet wines in a traditional way from grapes dried on bamboo mats.

But Chile is the real home of Criolla Chica or País, especially grown in the south in Maule, Itata and Bio Bio where there are huge plantings. País is the most important Criolla variety after Torrontés and was also a very early variety brought into Chile – there are still over 10,000ha of País here and recently there have been some new plantings, as interest grows on export markets. País is also being used increasingly as a rootstock, being resistant to nematodes, to help prevent Margarodes and able to cope with drought.

Today a lighter style of País is being made with less extraction, avoiding green tannins and once again different flavour profiles show through the different regions, however rusticity and red fruit character are typical. Artisanal techniques are increasingly being used again, even in some bigger wineries. Personally, I became a little over-excited when I saw the photos Amanda shared of the zaranda, a bamboo mat for gentle hand de-stemming (the traditional ‘crible’ a hand destemming device, used increasingly in the vineyards of the Jura is used in the same way). And it was extraordinary to me to learn that Chile is seeing a return to ageing in native Raulí wooden vats, which in the 1990s were mainly banished from cellars. Amanda showed us images of ancient País vines growing in a generally wild manner, up trees or head trained – one vineyard, which is still productive, goes back to the late 18th century.

The BOUCHON País Viejo 2020 we were given to taste is one of several País wines from Bouchon, and along with Torres this winery has been quite instrumental in the revaluing of País wines. To me it tasted rustic in the best possible way, balanced by plenty of fruit and highly structured too. Amanda notes that compared to Criolla Chica in Argentina there is more grip and freshness in Chilean País, and she recommended roasted meats or game dishes, even llama (!) as an accompaniment, or smoked potatoes for the vegetarians. She also noted that these wines are beginning to get recognition in the US, where there is appreciation of the social impact that buying these wines can have. Organic and sustainable viticulture is very important here.

Chile does not have the same strong wine culture as Argentina however it is strongest in the south of the country and this type of traditional wine production is a world away from how the industry giants work further north. Preserving and drinking País has an important social impact giving work to local farmers; it also has a cultural significance through the revival of traditional methods. Chile is in its 12th year of mega-drought so these old drought-resistant Criolla vines, are significant environmentally too – they are dry-farmed with low-impact techniques (such as ploughing by horse) and often organic.

Final comments and conclusions

Although research is underway to work on the family trees for the hundreds of Criolla varieties, there is no institutional focus anywhere on Criolla varieties, the revival is driven by producers. Yet the situation is fragile. Criolla varieties and old vines are being uprooted at a rapid rate in both Argentina and Chile, in particular due to declining local consumption, but also patchy demand on export markets. That said as well as the US interest in País, in the UK even Aldi is importing Criolla wines.

Amanda concluded that it is part of our responsibility as wine writers to take an interest in native varieties, because they support so many livelihoods and cultures as well as giving authentic expressions of South American wine regions. She shared some fascinating historical stories as well as a wealth of information in this webinar and during the question session that follows. For anyone interested in South American wines I urge you to watch and study the recording. And of course, buy and promote Amanda’s book or check her guide to Criolla varieties and A-Z to South American varieties on her website: https://southamericawineguide.com/.