Carla Capalbo is a respected expert in Georgian and Italian wine, having authored several books on the wine countries. Amanda Barnes interviews her about how she got into wine writing and why she’ll be making gingerbread again in lockdown.

What’s your earliest memory in wine?

I was born in New York City but I grew up in Paris and London and my stepfather had a wine cellar in our house on the river [Thames] in Chiswick, where he served Claret that he ‘put down’ each year. So I was lucky to have tasted good wine before I left for university, though nothing was ever discussed about it at home. At university at Sussex and as a post-graduate art student at St Martin’s, I was broke most of the time, so those years, when I worked as a waitress at the Hard Rock Café to pay for my sculpture studio, were mostly about cocktails and nondescript wine, alas.

After that I spent six years in New York City working as a food and prop stylist in photography and became more involved with food there, cooking and writing about it. By an odd coincidence, my mother, Patricia Lousada, had also become a food writer in the meantime, and when I’d visit London she would have fridges full of game or chocolate. She had a great palate and was interested in wine.

When did you move to Italy and how did you get into writing about Italian wine?

I moved to Italy in 1989 and, a few years later, began work on my first big travel book, The Food and Wine Lover’s Companion to Tuscany. The initial proposal didn’t feature wine but as I began my research I realised how central it was to Tuscany’s identity. I had no experience of tasting wines at that point. On my first visit to Fontodi, one of the greatest Italian estates, Giovanni Manetti spoke to me at length about his philosophy before asking if I’d like to taste the wines. I declined, asking instead to take a couple of bottles home with me. I couldn’t admit that I had no idea how to spit or write tasting notes!

Over time, I developed my own way of writing about wine, which focused as much on the producers’ stories and ideas about viticulture as what was in the glass. By the end of my work on that book I had visited over 100 Tuscan wineries and no longer felt like a novice. It also described over 500 other places – from restaurants to food shops, dairies, gelaterie and wine bars – and took three years of travelling from village to village to write. Around this time, I started writing for Decanter and I’m happy to say I still do today!

My next big Italian books – about Campania and the Collio in Friuli, which won the André Simon Wine Book Award – were also guides focused on the culture of rural food and winemaking. I lived like a nomad to write them, including spending six months in a fishing community on the Amalfi Coast and then several years in a mountain village among shepherds and chestnut growers in Avellino. I drove over 300,000 kilometres in my 20-year old VW bus. By now I was also illustrating my books with my photographs.

What drew you to specialise in Georgian wine and food over the past decade? And what do you think makes it a unique wine country and food culture?

I was becoming increasingly interested in a more holistic approach to food and winemaking, thanks too to my association with Slow Food. For my Collio book, I visited Josko Gravner’s small organic estate straddling the Italian-Slovenian border. He was the first non-Georgian to make wines in qvevri, the clay pots that have been Georgia’s historic winemaking tool for over 8,000 years. I was so moved by the energy in his cellars and wines that I vowed to go to Georgia to investigate further.

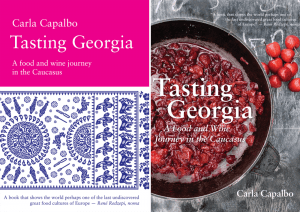

Thanks to friends at Les Caves de Pyrene I was able to, and that led to my somewhat madcap decision to write what turned out to be a very large book there: Tasting Georgia: A Food and Wine Journey in the Caucasus. While I did not then speak Georgian, I recognised many aspects of its rural agriculture from my time in southern Italy. That book, which is fully illustrated with my photos and includes 70 recipes, won several awards, including the Guild of Food Writers Food & Travel award, and is now in its third printing.

Thanks to friends at Les Caves de Pyrene I was able to, and that led to my somewhat madcap decision to write what turned out to be a very large book there: Tasting Georgia: A Food and Wine Journey in the Caucasus. While I did not then speak Georgian, I recognised many aspects of its rural agriculture from my time in southern Italy. That book, which is fully illustrated with my photos and includes 70 recipes, won several awards, including the Guild of Food Writers Food & Travel award, and is now in its third printing.

Like Carlo Petrini, who founded Slow Food in 1986, I see Italy’s wine future in its dozens of lesser-known indigenous grape varieties and in the young people who are now investing their time in reviving them in often overlooked areas. Similarly, the recent rediscovering of its wealth of native grapes, regional recipes and other cultural riches is what attracted me to Georgia. I’m drawn to less obvious places where the culture has remained strong and needs help with the communication. For instance, the south of Georgia, in Meskheti, is undergoing an exciting transformation as old varieties are being replanted in dramatic centuries-old terraces that were ripped out during the 300-year Ottoman occupation there.

You have written several food guides and cookbooks from Georgian cuisine to gingerbread. Will you be making some of the latter for the holiday season?

You have written several food guides and cookbooks from Georgian cuisine to gingerbread. Will you be making some of the latter for the holiday season?

I still love gingerbread and have used it to make tree decorations, labels for presents and place names for Christmas dinner over the years. Decorating it imaginatively is a perfect lockdown project.

You can find links to Carla’s books and writing on her website.