Stephen Skelton MW is one of the best-known authors of viticulture with his renowned and best-selling book, Viticulture. However, his knowledge and love of wine far surpass the vineyard, as Amanda Barnes finds out in this interview, in which Stephen shares his insights into making English wine, vineyard dogs and Japanese Ladybugs.

You had an interesting route into the wine industry as an English wine grower. How was the experience of getting into the English wine and grape growing industry in the 1970s?

To be honest I didn’t feel that me and my wife were doing anything very unusual! Of course, it was quite a momentous decision to strike out on our own on a completely new venture, but we had the significant backing of my father-in-law, for whom I had been working for three years since we got married, and who said he could supply the land for the venture, as long as we supplied the rest i.e. the hard work. We had met a few other English winegrowers – Peter Hall at Breaky Bottom, Robin Don at Elham Park, Richard Barnes at Biddenden, and Ken Barlow at Adgestone Vineyards, all of whom impressed us with what they were doing, so there were role models. We had also met other growers and winemakers who impressed us less, and we thought ‘we can do better than them’.

As for actually getting into the industry, after my two years in Germany I didn’t have any qualms about planting my own vineyard. The land we found had been approved and pronounced ‘perfect for vines’ and by then I had seen enough vines and new vineyards to know what to do. Once of course the grapes arrived, I then had to deal with the winemaking in which I had far less practical experience. But again, my friends in the industry were full of helpful advice and luckily, I spoke and read enough German to be able to learn the rudiments of winemaking.

Winemaking is actually just like cooking – ingredients, equipment, temperature and timing – get those right and you are almost there. Ingredients – grapes – are the main challenge in a marginal climate and I did my best to make sure we always had clean, ripe grapes and handled them appropriately. Winning the Gore-Browne Trophy for the ‘English Wine of the Year’ in 1980, with our second vintage, was a huge boost, as was the double page spread in the The Sunday Times magazine – the interviewer was one J. Robinson, their new wine writer.

How much do you think your experience in the marginal and challenging climates of England and Germany affected your decision to write on viticulture?

Not at all. I started with viticulture lectures for the WSET Higher Certificate in 1982, and then almost immediately began giving Diploma lectures after one of the WSET’s senior lecturers was severely injured in a road accident. I soon realised that there was a need for a short, non-technical book on viticulture and although it took me until I had stopped doing Diploma lectures for the WSET around 2006, I started to write what is today called Viticulture. To date, it has sold around 12,000 copies, which for a self-published, non-fiction book isn’t bad going.

With your update to Viticulture in 2020, what were some of the major changes in the world’s viticulture over the past decade that had to be considered?

Nothing very radical. A bit more on such things as GPS, IPM, and organic and biodynamic viticulture. It’s about 10-15% longer, but that’s because there’s an extra chapter on plant physiology as it was felt that the first edition was a bit lacking for beginners about how a plant actually works.

What do you envisage being the great changes or challenges to world viticulture in the next decade?

Well, climate change obviously, but it’s certainly not all negative. There was an MW Research Paper a few years ago about the effects of climate change on growers in the Northern Rhône, and they all basically thought it was a jolly good thing, and asked when they could start irrigating! Some regions will have to look at such things as the varieties they are allowed to grow, the trellising and training – especially vine density – they use, and such things as yield limits and irrigation.

For regions that have benefitted from climate change, the possibilities are endless and as we have shown in the UK, some new regions have flourished – although the UK still has problems of low yield levels. Other challenges will come from novel pests and diseases. Xylella fastidiosa (Pierce’s Disease) is very much here and damaging olive trees, and vines cannot be far behind. Japanese Ladybug, SWD (Spotted Wing Drosophila) and the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug are all on the warning list and a rise in temperatures can only increase their prevalence in previously free areas. Another area of change will be in GM (Genetically Modified) and GE (Gene Edited) vines. As soon as mainstream varieties that have been GE and that can be grown without spraying appear, then watch out for regions that are allowed to grow them (USA).

And are there any emerging viticulture regions that you think will expand or grow rapidly in the coming decade? Or likewise, regions that will shrink noticeably?

I imagine that most of the hitherto ‘marginal’ regions will grow, especially those with wine-loving populations, such as the UK and Scandinavian countries, plus the Netherlands and Belgium, but also the northern parts of Germany, Poland, etc. And in the more established winegrowing regions, vineyards will go to cooler parts and the higher parts. As for shrinking, well the hotter, high-volume parts of Europe have been shrinking for decades and this will continue. Italy, Spain and France will all shrink in their volume regions, but I cannot see high-quality, high-value regions shrinking much.

As a leading author on English wine with six guides on the subject, what do you think the greatest opportunities for English still wine are?

The UK winegrowing industry is a growing, moving, developing beast. Around 40-50% of all currently planted vineyards do not yet have wine for sale and over the next three to five years, the volumes being produced will double. And that is without any increases in planting. Planting is still continuing apace and there will be another 250-350 hectares going in in 2021. In 2018, we produced 13 million bottles and this could easily be doubled in 2021. Whether producers can sell 25 million bottles a year is another matter. Overseas wine producers are taking more interest in the UK, and there will be more plantings from non-UK companies.

The main varieties – Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Bacchus, Pinot Meunier – will stay on top, but with developments in Charmat wines, we will see more of the higher cropping varieties – Reichensteiner and Seyval blanc – being planted. We will also see more quality still wine varieties planted, such as Pinot Blanc and Pinot Gris, and the organic/biodynamic/sustainable bandwagon will continue to roll and PIWI and other hybrids will find favour with some growers. New reds like Divico, plus Rondo and Frühburgunder will continue to increase in area, as will Solaris.

As for regions, the higher-yielding, drier areas of the UK – Essex and East Kent – will expand even further and become more and more dominant. At the moment South East and East Anglia have around 75% of vineyards by area and this will grow. Yields, yields, yields are what keeps winegrowing profitable. Not high yields, but viable, sustainable yields.

And do you think English still wine will achieve any international success or remain mainly for the local market?

With 40 million wine drinkers plus 10-15 million wine-drinking tourists when they return, the UK will always be the dominant market. Exporting is expensive, low volume at least to start with, and export markets need servicing. Many of the bigger UK vineyards have tried, but from what I see, most of them think that wine tourism, wine-related visitor attractions and direct to consumer sales are more important than exports.

What is in the pipeline for you this coming year?

Viticulture has been translated into Japanese and the National Research Institute of Brewing (NRIB) in Hiroshima have ordered 1,000 copies as they are starting a new wine course and this is their text book for the viti section. It has also been translated into Chinese and is being published by the China Agriculture Press in 2022.

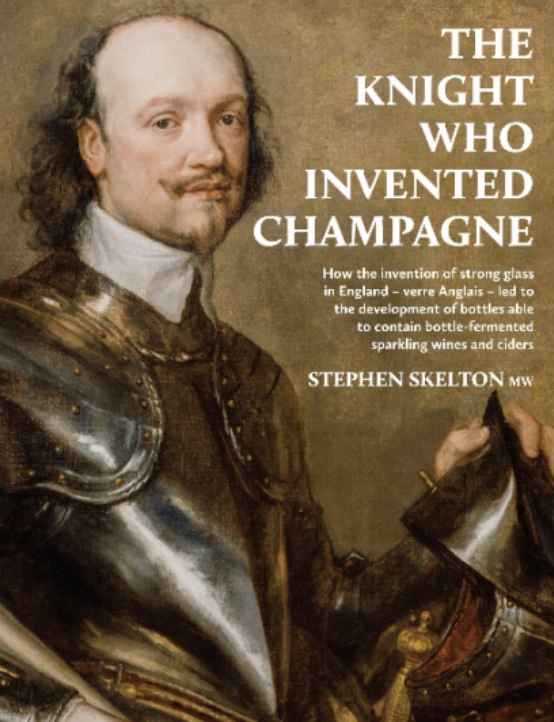

My next book is called The Knight Who Invented Champagne and is being published in April 2021. My book after that is Great British Vineyard Dogs which is – wait for it – a book about vineyard dogs and their owners.

When normal travel resumes, is there any wine region that is on the top of your list to visit? And why?

Not really. I don’t write on non-UK wines, I don’t sell wine at all, and I have never worked abroad [with the exception of Germany early on]. I would like to visit Western Australia one day and with the 2022 MW Symposium hopefully taking place in Adelaide, this might provide a chance to visit Perth and the Margaret River region.