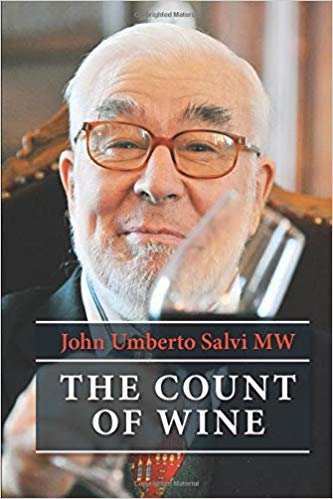

Neil Fairlamb reviews The Count of Wine by John Umberto Salvi (available from Amazon UK) and reflects on his fascinating life in wine.

This has to be the bargain of the year, at £4.99, indeed of the decade at least. For the price of plonk you have Premier Cru quality of anecdote, history and wine wisdom. Every page is full of precise detail, vivid personalities, frequent hilarity, sometimes painful honesty and, throughout, a determination to seek out the best. John has been a Master of Wine since 1970; his wine expertise, though, honed over these 50 years of MW status, has merely confirmed the promise of one of his first sips of wine when, aged a little past his eighth birthday in 1945, his father allowed him a small measure of Vosne-Romanée which he sniffed, swirled and sipped before declaring, to the astonishment of his father and the sommelier, “this wine needs another ten years before it will be ready to drink”. Shortly before this, still barely eight years old, he had sipped a Château d`Yquem at the property with his father: he had started as he meant to go on, with the best.

John followed his father into the trade and, after Westminster School and National Service (including GCHQ, and learning Russian, and an alarming five days in Hungary in 1956) he started as a trainee with Maison Sichel in Bordeaux, and his first duty was to help with the 1957 vintage at Château Palmer in Margaux, close to where he lives now with his wife Petronella. It was a difficult vintage and the pages on traditional winemaking in the 1950s are revelatory; nobody had heard of malolactic fermentation, for instance. He worked solidly for two years before being sent to work for Maison Sichel in England. He asked for a short break in Pamplona for the bull-running Fiesta San Fermin; there he saw an enormous man and told his friends, “Ye Gods, he looks exactly like Hemingway.” Indeed he was. John was invited the next day to sit at his feet while the Master drank Cuba Libres and held court: two years later he shot himself (typical of John, he knew the man who bought the gun).

John became a salesman for Sichel in the Midlands and North of England, mixed with buying trips to Languedoc, the Midi and the Loire; there were never any wine glasses carried or provided and everyone had a silver tastevin. Aged only 28, he was invited to join the Board of Directors of Maison Sichel; he celebrated with two bottles of Krug 1928, which cost a month’s salary. He became Sales Director for the company, living in, and working from, Château Palmer itself. He took his Master of Wine exams five times before passing; it cost £12.50 to take the exam. Now it probably costs £1250-or more. At his third attempt there was a sherry to identify in a blind tasting; this was no problem for John who knew it well, a Dos Cortados from Williams and Humbert. He knew it too well, however, and so enjoyed drinking most of the bottle during the exam there was barely enough for the other candidates to taste. He was proud to be censured for ‘conduct unbecoming a future Master of Wine’.

You must read for yourselves the difficult years for both Bordeaux, in general, and for John himself after 1970; he recovered from a painful divorce and was rescued from a serious alcoholic phase by his wonderful and committed second wife Petronella, to whom the book is dedicated, and who has, in a lovely phrase, ‘made my life worthwhile’. He returned to Margaux after a difficult parting with Peter Sichel (well, John had taken a 1928 Yquem from the private cellar at Palmer to drink over Christmas), and a financially hard time for five years, and then worked as a quality Bordeaux négociant for Mӓhler-Besse who had the controlling interest in Château Palmer. This was followed by his ‘retirement’ career as a writer, a consultant, a judge, and especially frequent visitor to the Far East, South Africa, USA, and international fame as a taster of unsurpassable experience.

The second half of his wine memoir is full of tributes to, and anecdotes about, people in the wine trade and wine press, beginning with one of the other two ‘little pigs’, Martin Bamford, who, with John and John Davies, were legendary in Bordeaux for insistence on the best of everything in food and wine. The account of Pamela Vandyke-Price deciding to do her exercises at the end of lunch at Château Palmer will have you in fits of laughter; she lay down on the floor and kicked out so vigorously she knocked over the coffee table showering herself with hot coffee, cream, sugar and broken cups and saucers. Not your or my image of Lady P (‘Prudent be’)!

Does John have a philosophy of wine? Yes, he asserts, it is ‘vilely selfish…always drink your friends’ wines of a particular provenance and vintage until you find they are ready to drink and then start drinking your own!’ Whatever you choose to drink when reading this memoir, make sure it is a very fine wine worthy of its author but sip slowly as you`ll be gurgling with delight and admiration at John’s powers of recall and characterizing everyone he writes about with appreciation, candour and affection.

Review by Neil Fairlamb