Steve Pryer visits Italy to explore the facts, figures and reasons why the tsunami of easy-drinking, affordable Italian sparkling wine has changed the drinking habits of many Britons.

Prosecco has been the UK’s bubbly sensation of recent years. Despite some recent reports of a slow-down in sales, the UK remains one of biggest buyers of this Italian sparkler, purchasing more than one-third of all prosecco produced (UK sales nearly doubled every year between 2011 and 2017).

Northeast Italy, amid the gentle hills to the south of the Dolomites, is home to prosecco in the regions of Veneto and Friuli Venezia Giulia; here nearly 30,000 hectares of vines produce some 550 million bottles a year. These wines are governed by two appellations/producer associations formed in 2009 that regulate consistency and quality – Prosecco DOC and DOCG.

The DOCG claims to make the highest-quality prosecco in an area of 8,880 hectares centred on the Conegliano and Valdobbiadene district. Here there are 3,387 growers, 433-plus winemakers (of which 181 are sparkling houses), making 94 million bottles a year. These vineyards are nearly all on steep (sometimes vertiginous) slopes where handpicked, mainly Glera grapes yield 13.5 tonnes per hectare.

Top of the DOCG pile comes the 106 hectares of Cartizze – a triangular, steep-sided hill regarded as the ‘grand cru’ of prosecco (Cartizze has more than 100 growers each with less than a hectare – with every hectare valued at more than two million euros – yep, they are pretty much impossible to purchase). Picking grapes here can be dangerous, the soil is loose (and well-oxygenated, which contributes to quality) and the slope so steep that no tractors can ever be used and special wooden benches are needed to stand on when harvesting (indeed, I felt more than a twinge of vertigo standing on a level track looking downhill beneath the rows of vines).The resulting yield is a very high-quality 12 tons per hectare; the prosecco produced is some of the best I have tasted.

Also within the DOCG are the 574 hectares of Rive – a word in the local dialect that refers only to sparkling wines from hand-picked vines coming from a single village or hamlet. Finally, there are 7,700 hectares in 15 municipalities around Conegliano Valdobbiadene, the ‘engine room’ of the DOCG – to my mind wines well worth looking out for, despite a relatively small (and justifiable) price premium.

There are clear stylistic variations within these three parts of the DOCG, well worth exploring and, for my money, some of the most vivid and interesting prosecco made.

Prosecco DOC (whose consortium takes on a huge spectrum of promotional, cultural and voluntary work – and kindly hosted this visit) covers the majority of prosecco production in Italy with 24,450 hectares under vine (19,922 in the Veneto and 4,528 in Friuli Venezia Giulia – split again another way into 556 municipalities in Prosecco DOC and 95 municipalities of Prosecco DOC Treviso).

The whole DOC represents 10,242 growers, 1,149 winemakers (348 sparkling houses) making some 440 million bottles a year. The DOC has an average vineyard yield of 18 tons per hectare. Turnover for the whole of the DOC is an estimated 2.1 billion euros a year. Prosecco DOC, given the many bottles I tasted from a variety of producers, is a remarkably dependable and enjoyable fizz; its delicious reliability will doubtless be the mainstay of its future.

Virtually all wines sampled showed an incredible evenness of colour, straight and fresh taste and bright, bubbly and balanced mouthfeel, together with an amazing array of aromas and flavours – the almost ubiquitous apple, pear and citrus notes (and occasional classic sweet-shop flavours of bubblegum, pear drop and banana cream) were often paired with surprising and elegant floral notes, hints of acacia, wisteria and tropical fruit. Surprising and delicious.

Look out for the special brown neck label when buying DOCG prosecco and a similar blue neck label for the DOC. These guarantee authenticity – don’t get conned by fake prosecco it can be (and often is) dreadful.

Recent research suggests sales of prosecco in the UK show a definite split between north and south with, per capita, more being sold north of the Watford Gap. Does this represent a dichotomy largely based on austerity/relative wealth? Prosecco is an obvious choice if you seek consistent, delicious fizz at affordable prices. It is certainly a democratic purchase. During a decade of austerity, neoliberalism and reduced family budgets, it’s not too hard to understand why millions of bottles of interesting, delicious, good-value bubbly have hit the mark. The DOC openly admits its main UK targets are millennials and women. So you might conclude these younger northern women know their stuff!

There are stringent regulations in prosecco production; the Glera grape (once known as prosecco and most probably a historical import from next-door Slovenia) is the ‘backbone’ and must make up a minimum of 85% of the wine; it is a prolific, large, loosely-packed, often bright-yellow grape. Other varieties can be used up to a maximum of 15%; these include local varieties such as Verdiso, Bianchetta Trevigiana, Perera and Glera Lungi; international varieties such as Pinot and Chardonnay can also be utilised.

Differing types of prosecco are split into three: still (tranquillo), semi-sparkling (frizzante and rifermentato in bottiglia) and sparkling (spumante). Still wine only accounts for a minute percentage of total production (0.05%). All the rest fizzes in one way or another.

The style of prosecco is determined by the levels of residual sugar in each wine. Hence:

Brut is the driest with between 0 and 12 grams of sugar per litre and represents 25% of the current market (and is the area of extreme interest to the winemakers I spoke to; this part of the market appears, pro rata, to be expanding the fastest).

Extra Dry (confusing by name, I know) has between 12 and 17 grams of sugar per litre. This is the most famous style of prosecco and owns 63% of sales.

Dry has between 17 and 32 grams of sugar per litre and accounts for 10% of the market.

Demi-Sec is the sweetest of the lot with between 32 and 50 grams of sugar per litre, accounting for just 2% of sales. For my palate, there is a great market for this as a pudding-matcher.

All of these proseccos are made using the Metodo Italiano, Metodo Martinotti, Charmat Method (all the same, just different names) whereby, after harvest, de-stemming and pressing, the grape juice (with yeast) is put into temperature-controlled stainless-steel tanks for primary fermentation. When fermentation is complete, the wine is put into separate stainless-steel tanks for a minimum of 30 days secondary fermentation (triggered by adding yeast, cane sugar and/or more grape juice). When the right alcohol level is hit (usually around 11%), the final product is stabilised, filtered and the stable, clear wine is bottled under pressure.

Hot tip: All of these wines are designed to be consumed within 18 months of purchase. So don’t hide them away in some cobwebby recess and forget about them.

One small exception to this Charmat production technique is Col Fondo (literally ‘on the bottom’). Instead of creating bubbles in steel tanks, these more-traditional versions undergo secondary fermentation in the bottle (like champagne or cava). They aren’t disgorged, and wines are bottled on their lees leaving a sediment which gives depth, complexity and intense flavours to the wine. Interesting stuff but don’t drink all of that last glass from the bottle (as I did).

Tanja Barattin of the Prosecco DOC consortium gave some fascinating insights into future activities in the region. She explains that quality, plus environmental, social and economic sustainability, are all high on their hit-list. Beyond that, the prosecco name must be protected and new markets need to be explored. “Our producers are adding up to 1,500 hectares of vines each year, so we hope to keep demand high,” she says.

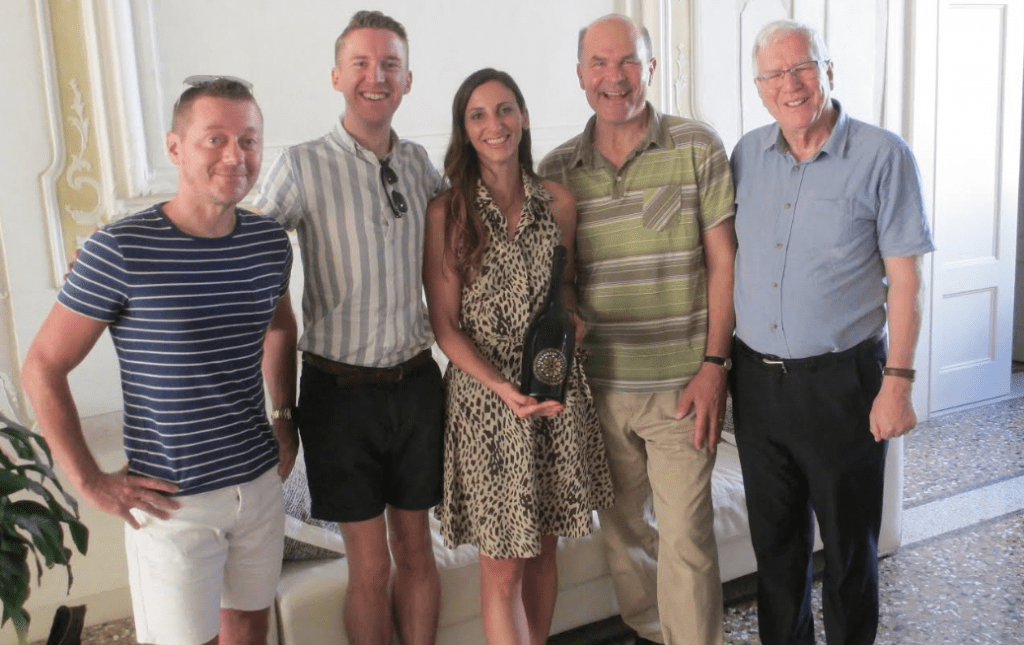

A huge thank you must go to the delightful Tanja and her captivating co-conspirator at Prosecco DOC, Arianna Pizzolato, for arranging such an outstanding and interesting trip. You might imagine a ‘one product’ visit to be repetitive and boring; well, that’s exactly what it wasn’t.

Add to that the wonderful company of charming, walking encyclopaedia Keith Grainger; the hugely witty writer (and great Welsh tenor) Ross Clarke; brilliant Chris Walkey, founder of the Glass of Bubbly website and the only man I’ve ever met who really understands social media; and, of course, tour leader, the charismatic and redoubtable wine tipster himself, Neil Phillips, who always led from the front (if you ever need to stop a runaway horse, Neil, just bet on it!)

As mentioned above, the prosecco area has a huge number of wineries; many are justifiably renowned for exceptional quality – but today’s overall bulk production is more than notable with larger producers and brands revealing phenomenally clean, interesting wines. Investment in up-to-date technology is paying dividends and a happy global audience (particularly in the UK) is enjoying the outstanding standards and reliability of modern prosecco. The worldwide spread of Italy’s favourite sparkler is destined to continue.

Of goodness-knows-how-many bottles tasted during five packed days in the region, not one showed any clear evidence of fault. I may have picked up the slightest reductive whiff of burnt match/rotten egg on a couple of offerings (oxygen during production is, of course, the enemy of these wines and eliminating it can have these side-effects) but that would be really nit-picking. Overall, standards were stratospheric.

Having been a stalwart lover of decent champagne for many decades, I am now also an ardent lover of good prosecco – a genuine convert (and I’ve convinced several more since my return). There’s no confusion in this; one is not a cheaper version of the other. They are entirely different products and should be drunk and enjoyed exactly as that. I shall delight in both, I hope for many years to come.

A hectare of prosecco vines tops two million Euros

Standing amid the majesty of the upper slopes of Cartizze – the ‘golden triangle’, a small hill and sub-zone of Valdobbiadene in glorious afternoon sunshine, one might dream of owning a modest slice of this winemaking paradise. This is, after all, the ‘grand cru’ of all Prosecco wines in north east Italy.

Yet even a billionaire tech-business owner, Russian oligarch or Amazon chief Jeff Bezos with £150 billion in his back pocket won’t get a look in. The 106 hectares of Cartizze, owned by 110 individual growers, are estimated to be worth at least 2 million euros each. Even so, nobody’s selling. This land is owned by families who are either related or very close friends and neighbours. As each generation passes, the parcels of inherited land inevitably get smaller and smaller and the chance for an ‘outsider’ to buy reduces.

Paolo Bisol, owner of Ruggeri, and his delightful daughter Isabella, show me two glera vines on the precipitous Cartizze slopes: “This one is probably about thre e years old,” says Paolo.” He then points to the one next to it in the row: “And this one is probably more than 90 years old.”

e years old,” says Paolo.” He then points to the one next to it in the row: “And this one is probably more than 90 years old.”

Isabella explains that, unlike most vines in the overall prosecco producing area, these vines are not replaced every 30 years or so. The land is so steep that vines are never affected by tractors or any machinery, so the soil is less compact and will give the vine more oxygen. This tends to lengthen the life of each vine. When one vine dies off, it is replaced by another single vine. This means that the vineyards become disetaneo meaning ‘ageless’. With vines planted at different times, it’s impossible to know their actual age.

The Ruggeri winery produces one million bottles each year. The firm has two small vineyards in Cartizze and 20 hectares on nearby Montello, and also takes grapes grown by more than 100 growers. In 1993, the original winery in the heart of Cartizze was moved to new, larger premises. Great wines tasted included Vecchie Viti Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore DOCG Brut – made from 80- to 100-year-old vines scattered over the local hills. This wine is left in contact with the yeast until just a few days before bottling, reflected in the delicious minerality and slight saltiness on the palate. Sadly, only 5,000 bottles are made of it each year.

More wineries worth visiting

The range of wines from Antonio Facchin and Figli proved exciting (and highly favoured by Oxford University, we hear). Our visit also coincided with La Vendemmia Social-e (the social harvest), a charity event raising funds for patients recovering from the effects of oncology. Great company paired with delicious food and wine to match.

Owned by the charming Ceschin family, the winery at Sanfeletto again showed terrific wines – the driest, Bosco Di Fratta Millesimato Brut with less than three grams of sugar per litre had subtle mineral-and-grapey notes, elegance and finesse. Longer secondary fermentation breaks down nearly all the sugars. The family have been growing, harvesting and making wines for three generations.

The Oenological School of Conegliano (which is linked to the University of Padua) proved well worth the visit. It has been fundamental to the success of Prosecco DOC/DOCG. We tasted wines created by students and learned the answer to one nagging question: where do all this region’s talented winemakers come from? Now we know.

Astoria is one of the region’s medium-to-large producers (and biggest private producer), selling 60% to the Italian market and 40% for export (mainly USA, UK and Scandinavia). It has a great track record and produces eight million bottles each year from its 40-hectare Val De Brun Estate, plus contributions from more than 100 growers who supply some 5,500 tons of grapes. Astoria has superb branding and advertising plus a range of colourful, fun and arrestingly designed bottles all on show in the modern shop at the entrance to the winery.

The family Moretti Polegato own and run Villa Sandi and have more than a few aces in the pack to play with. The winery headquarters is a stunning Palladian villa dating back to 1622, which characterizes the Venetian landscape of past centuries. Villa Sandi Estates stretch over several areas, from the wider DOC, to the gentle hills of Asolo DOCG, to the steep slopes of Conegliano-Valdobbiadene DOCG, to the special cru of Cartizze in Valdobbiadene. The range of wines here is top-notch and includes some personal favourites (the Millesimato Brut DOCG is one). Villa Sandi has also been certified as a Biodiversity Friend, confirming the winery has minimal impact on the environment. It is well-regarded for good practice in wine growing and is recognized for its attitude towards green issues, such as sustainability, use of renewable energy (hydroelectric power plant, water purification plant and photovoltaic system), reducing CO2 emissions, hedging and conservation.

Geographically more remote than most major Prosecco wineries, Borgoluce in Susegana near the Piave river, is somewhere I’d definitely hope to revisit. This is an estate in every sense of the word; it’s huge. The ultra-modern winery is merely one aspect of the business. Here you find true heritage: exceptional wines (prosecco, red and white), meat, buffalo mozzarella (and numerous other cheeses), walnuts, flour, oil and honey – all reflecting the local environment and all available from the farm shop. A farmhouse holiday at Borgoluce (and a re-taste of all its wines and foods at leisure) sits paramount on my wish list.

The winery Marcello del Majno in Fontanelle is a family-owned estate centred on a villa dating back to the end of the 17th century, originally used as a hunting pavilion for the Tiepolo family. Also, the largest outbuilding (the Finlanda) here was historically used for silk production. The old granary has a fine collection of ancient coaches and agricultural equipment. Captivating Alessandra Niccolini (one of the family) escorted us around this fine property; it has 60 hectares of vineyards producing a range of wines of great personality and quality – the 85% Glera/15% Pinot Bianco Prosecco Villa Marcello Extra Dry is outstanding.

Maccari Spumanti in Conegliano began in 1898 and today owners Silvia and Filippo Maccari are proud to still make a wide range of wines “driven by passion, commitment, tradition and creativity”. Much of the firm’s hefty production (90%) is sold to the Italian domestic market in contemporary steel kegs – wines include Sauvignon, Tai, Pinot Bianco, Verduzzo, Chardonnay, Spinolo (white and red), Cabernet, Rabosino, Provis and Glera. Maccari also makes some two million bottles of sparkling wine a year, including several award-winning proseccos, this year marking 120 years of winemaking.

Yet more dedicated and sumptuous winemaking is found at Fantinel near the Slovenian border in Pordenone – for my nose and palate, these are very good across the board. Deliberately lower yields (around 75 hectolitres per hectare, compared with up to 120 in some other of the region’s vineyards) make the wines more authentic, longer in the mouth and deeply fruit-driven. Chief executive Marco Fantinel explains that Fantinel has some 300 hectares of vineyards, of which 80% are machine harvested. Only 10 hectares for the ‘One and Only’ brand is harvested by hand. “The microclimate and terroir in Friuli produce a different style of Glera grape,” Marco explains. “We are only about seven kilometres from the Dolomites to the north and our vines lie between two rivers; much of our soil has big stones and the ground gives our two main clones great acidity. Thank God there are people who care about what they buy,” says Marco. Interestingly, Fantinel distributes around the globe but the UK remains its biggest market.

Thinking banana

It is easier to get distracted as one gets older. During some deep-and-meaningful conversation in Italy about particular prosecco flavours, we chewed the cud over the oft-used description of ‘banana cream’. What is it exactly? Thoughts included the smell of banana milkshake through to the distinctive aroma of banana squashed together with double cream. Resolving nothing, but apropos ‘Banana’, my mind wandered back more than 20 years to the news that Zimbawe’s first president Rev Canaan Banana (replaced by Robert Mugabe) had been accused in a sex scandal. I recalled some bright spark on the Durban evening paper headlining its front page: ‘Banana in custody’.

Battling the fizzes of Oz

Most British prosecco lovers perceive that their well-loved Italian sparkling wine comes from the region of the same name in Italy – Prosecco DOC and DOCG are the protected appellations under EU regulation. Yet Italy’s producers have a fight on their hands – with Australia.

The Aussies, with a strong Italian heritage, make their own version of prosecco, first planted in King Valley near Melbourne, and have done so for more than two decades – long before Prosecco DOC was officially created in 2009 when the local Italian regulators, in a bid to avoid confusion, also changed the grape’s name from prosecco to uncommonly ugly name ‘Glera’.

The Australians view that name change as somewhat arbitrary and continue to argue for their right to call their wines prosecco. They, apparently, stand to lose a lot of money if they have to drop the name.

Prosecco DOC says negotiations are continuing and there are planned, high-level meetings in Canberra which, with luck and a fair breeze, may see the problem resolved.

I wouldn’t want to see either side out-of-pocket but having recently seen how hard the charming, dedicated and resourceful Italian winemakers are working to make terrific prosecco, I hope their arguments are heard favourably and a fair compromise is reached.

Are you exhausted by making decisions? Apparently, this is a real problem in modern society. What to wear, where to go, what to eat, what to drink? Researchers at Cornell University estimate we form 35,000 conscious choices every day; 226.7 of those are about food alone. How long does it take to choose and say ‘prosecco’? A split second, I guess.

By Steve Pryer